From Zones of Oppression

1993Living with Tourism

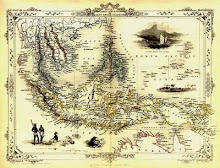

MULU NATIONAL PARK, SARAWAK, MALAYSIA - First the startling and strange signs appear: "No trespassing or encroaching into our NCR land." Then, up the Melinau River toward Mulu National Park, comes an even more bizarre sight: a complex of posh bungalows, each with its own air conditioning units, deep in the jungle of Sarawak's interior.

The signs, erected by the Berawan people, a small indigenous ethnic group of approximately 1,000 people, draw the battleline in a land conflict that pits the Berawan against a Japanese hotel chain and the Sarawak state government. The bungalows rest on the non-Berawan side of the battleline; they comprise the Royal Mulu Resort, a five-star hotel for wealthy visitors to the breathtaking Mulu National Park.

Opened to foreign tourists in 1985, the park features the spectacular Mulu cave system, which includes the world's largest cave chamber. A recently constructed airstrip bordering the park makes this remote area far more accessible to outsiders than it was only a few years ago. Visitors can stay at low-priced tourist hostels run by Berawan entrepreneurs or at the Royal Mulu Resort which bills itself as offering "Adventure in the Lap of Luxury" and assures potential customers, "You won't be living in a tree-house in Mulu." Rooms at the luxury hotel, which is owned by local interests and operated by the Rihga Royal chain, cost from $100 to $800 a night.

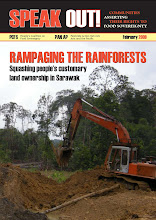

Now the resort owners have provoked a conflict with the Berawan by preparing plans to expand the hotel and to construct a 200-acre golf course on land the Berawan claim is their ancestral, or Native Customary Right (NCR), land. The state government has lined up on the side of the hotel, a fact the Berawan link to the significant stake that family members of Sarawak's chief minister have in the hotel.

For the Berawan, the fight is the latest chapter in a decades-long struggle against "development projects." Like so many indigenous Dayak people in Sarawak, the Berawan have seen their means of survival undermined by the widespread logging of Sarawak's forests, which has deprived them of food and medicines and led to soil erosion and pollution of the rivers where they traditionally have fished.

While the Berawan-hotel dispute centers on a relatively small piece of territory, it is disturbingly representative of indigenous land conflicts in Sarawak. The Berawan themselves cast the conflict in broad terms and believe they are fighting on behalf of the state's entire indigenous population. "We feel that if the government can do this to us, it can do the same to native land anywhere in Sarawak," says Thomas Ngang, a leader of the Berawan.

Ancestral rights vs. family ties

The Berawan have strong evidence of their historic ties to the land for the proposed golf course. The land contains many markers of traditional Berawan use, including the remains of an old long house, a burial site and old gardens and fruit trees belonging to the Berawan, claims Ngang. It also, he adds, "is in the area where we hunt."

Representatives of the hotel in Mulu were unavailable for comment, and the Tokyo office of the Rihga Royal chain declined to respond to questions about the Berawan claims.

But the state government has been vocal in its refusal to recognize the Berawan land claim, with officials calling the Berawan "squatters" and "greedy people." Ngang retorts, "If we are squatters, the government should drop the chief minister and me in the Mulu cave and see who can find their way back." The state government says it is free to permit the hotel to use the disputed land, which it calls state land, as it wishes.

The Berawan charge that the government is refusing to recognize their NCR land because of the Sarawak chief minister's ties to Borsarmulu, the local company which owns the hotel. Lawyers hired by the Berawan have documented that the chief minister's brother, sister and brother-in-law sit on the board of directors of Borsarmulu. This sort of conflict of interest is typical in Sarawak, where the economy is dominated by small politically connected cliques, and it poses obvious difficulties for opponents of state- approved development projects.

Resisting the resort

With the government refusing to entertain repeated appeals for recognition of their land claims, the Berawan have resorted to various protest activities.

Since July 1992, they have temporarily blockaded the pathway to the resort's fuel storage area on several occasions, preventing oil from being delivered to the resort and threatening the resort's ability to continue operating. The Berawan held their most recent blockade during the last week of July and first week of August, with some of the Berawan who work in Sarawak's oil industry giving up their jobs in order to help staff the barricade.

Many Berawan work as guides for the national park, and they have tried to use their positions to advance their cause. The guides explain the Berawan concerns to all tourists, and ask the tourists to urge the government to recognize the Berawan NCR land claim. On August 2, in an attempt to increase the pressure on the government to recognize their land claims, the guides went on strike, essentially shutting down the national park, since tourists are not allowed to enter the park without a guide.

The Sarawak government's initial response to the Berawan's latest expression of militancy was forceful and unwavering. As the conflict heated up in the beginning of August, the police arrested a handful of people blockading the resort's fuel storage area and deployed more than a dozen paramilitary forces to the park. Awang Tengah Ali Husan, assistant minister in the Sarawak chief minister's office, told the Borneo Post, "The unsubstantiated claims by the Berawans will not be entertained even though the Mulu tribe has been staging strikes and protests."

Whether the government will maintain its hard-line position is unclear. The Berawan ultimately called off the August blockade, reportedly after the government announced that it would not negotiate with them if the protests continued. Although no date has been set for negotiations, the Berawan are hopeful that the government has softened its stand - but they are committed to resuming protests if the government refuses to enter a good-faith dialogue.

Development and dignity

The Berawan are careful to stress that they are not "anti-development." They support development of the national park as a tourist attraction - many of them now rely on tourism for their economic well-being - but they want their land rights recognized, and they want to be actively involved in decision-making about how land near the park will be used.

A leaflet distributed by the Berawan at the August blockade explained what is at stake in their fight: "It is a question of economic survival, and the defense of our fundamental rights to live as a people with dignity." For a people who have already seen their way of life profoundly changed by logging "development," the struggle over tourism at Mulu National Park may be the last opportunity to defend and assert their ancestral and community rights.

The signs, erected by the Berawan people, a small indigenous ethnic group of approximately 1,000 people, draw the battleline in a land conflict that pits the Berawan against a Japanese hotel chain and the Sarawak state government. The bungalows rest on the non-Berawan side of the battleline; they comprise the Royal Mulu Resort, a five-star hotel for wealthy visitors to the breathtaking Mulu National Park.

Opened to foreign tourists in 1985, the park features the spectacular Mulu cave system, which includes the world's largest cave chamber. A recently constructed airstrip bordering the park makes this remote area far more accessible to outsiders than it was only a few years ago. Visitors can stay at low-priced tourist hostels run by Berawan entrepreneurs or at the Royal Mulu Resort which bills itself as offering "Adventure in the Lap of Luxury" and assures potential customers, "You won't be living in a tree-house in Mulu." Rooms at the luxury hotel, which is owned by local interests and operated by the Rihga Royal chain, cost from $100 to $800 a night.

Now the resort owners have provoked a conflict with the Berawan by preparing plans to expand the hotel and to construct a 200-acre golf course on land the Berawan claim is their ancestral, or Native Customary Right (NCR), land. The state government has lined up on the side of the hotel, a fact the Berawan link to the significant stake that family members of Sarawak's chief minister have in the hotel.

For the Berawan, the fight is the latest chapter in a decades-long struggle against "development projects." Like so many indigenous Dayak people in Sarawak, the Berawan have seen their means of survival undermined by the widespread logging of Sarawak's forests, which has deprived them of food and medicines and led to soil erosion and pollution of the rivers where they traditionally have fished.

While the Berawan-hotel dispute centers on a relatively small piece of territory, it is disturbingly representative of indigenous land conflicts in Sarawak. The Berawan themselves cast the conflict in broad terms and believe they are fighting on behalf of the state's entire indigenous population. "We feel that if the government can do this to us, it can do the same to native land anywhere in Sarawak," says Thomas Ngang, a leader of the Berawan.

Ancestral rights vs. family ties

The Berawan have strong evidence of their historic ties to the land for the proposed golf course. The land contains many markers of traditional Berawan use, including the remains of an old long house, a burial site and old gardens and fruit trees belonging to the Berawan, claims Ngang. It also, he adds, "is in the area where we hunt."

Representatives of the hotel in Mulu were unavailable for comment, and the Tokyo office of the Rihga Royal chain declined to respond to questions about the Berawan claims.

But the state government has been vocal in its refusal to recognize the Berawan land claim, with officials calling the Berawan "squatters" and "greedy people." Ngang retorts, "If we are squatters, the government should drop the chief minister and me in the Mulu cave and see who can find their way back." The state government says it is free to permit the hotel to use the disputed land, which it calls state land, as it wishes.

The Berawan charge that the government is refusing to recognize their NCR land because of the Sarawak chief minister's ties to Borsarmulu, the local company which owns the hotel. Lawyers hired by the Berawan have documented that the chief minister's brother, sister and brother-in-law sit on the board of directors of Borsarmulu. This sort of conflict of interest is typical in Sarawak, where the economy is dominated by small politically connected cliques, and it poses obvious difficulties for opponents of state- approved development projects.

Resisting the resort

With the government refusing to entertain repeated appeals for recognition of their land claims, the Berawan have resorted to various protest activities.

Since July 1992, they have temporarily blockaded the pathway to the resort's fuel storage area on several occasions, preventing oil from being delivered to the resort and threatening the resort's ability to continue operating. The Berawan held their most recent blockade during the last week of July and first week of August, with some of the Berawan who work in Sarawak's oil industry giving up their jobs in order to help staff the barricade.

Many Berawan work as guides for the national park, and they have tried to use their positions to advance their cause. The guides explain the Berawan concerns to all tourists, and ask the tourists to urge the government to recognize the Berawan NCR land claim. On August 2, in an attempt to increase the pressure on the government to recognize their land claims, the guides went on strike, essentially shutting down the national park, since tourists are not allowed to enter the park without a guide.

The Sarawak government's initial response to the Berawan's latest expression of militancy was forceful and unwavering. As the conflict heated up in the beginning of August, the police arrested a handful of people blockading the resort's fuel storage area and deployed more than a dozen paramilitary forces to the park. Awang Tengah Ali Husan, assistant minister in the Sarawak chief minister's office, told the Borneo Post, "The unsubstantiated claims by the Berawans will not be entertained even though the Mulu tribe has been staging strikes and protests."

Whether the government will maintain its hard-line position is unclear. The Berawan ultimately called off the August blockade, reportedly after the government announced that it would not negotiate with them if the protests continued. Although no date has been set for negotiations, the Berawan are hopeful that the government has softened its stand - but they are committed to resuming protests if the government refuses to enter a good-faith dialogue.

Development and dignity

The Berawan are careful to stress that they are not "anti-development." They support development of the national park as a tourist attraction - many of them now rely on tourism for their economic well-being - but they want their land rights recognized, and they want to be actively involved in decision-making about how land near the park will be used.

A leaflet distributed by the Berawan at the August blockade explained what is at stake in their fight: "It is a question of economic survival, and the defense of our fundamental rights to live as a people with dignity." For a people who have already seen their way of life profoundly changed by logging "development," the struggle over tourism at Mulu National Park may be the last opportunity to defend and assert their ancestral and community rights.

No comments:

Post a Comment