ANTIDOTE Why did rural Sarawakians and Sabahans stay with BN, while their urban counterparts voted overwhelmingly for change?

BN's strategy of carping on ethnic insecurities made no impact in Borneo, yet BN won 48 of 57 parliamentary seats in Sabah, Labuan and Sarawak.

In

Sarawak, even allowing for electoral fraud, it was clear that the

"urban tsunami" stopped at the coastal towns of Kuching, Sarikei, Sibu

and Miri.

In

Sarawak, even allowing for electoral fraud, it was clear that the

"urban tsunami" stopped at the coastal towns of Kuching, Sarikei, Sibu

and Miri.

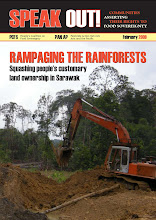

Rural Sarawakians have been denigrated as "squatters" on their own land.

Many have had their native customary rights (NCR) land stolen, their NCR defenders assaulted with machetes, their daughters raped, their air and rivers polluted, and their lawyers detained without charge.

BN's strategy of carping on ethnic insecurities made no impact in Borneo, yet BN won 48 of 57 parliamentary seats in Sabah, Labuan and Sarawak.

Rural Sarawakians have been denigrated as "squatters" on their own land.

Many have had their native customary rights (NCR) land stolen, their NCR defenders assaulted with machetes, their daughters raped, their air and rivers polluted, and their lawyers detained without charge.

Some

political commentators insist that rural Sarawakians and Sabahans are

"stupid" - and proclaim their own stupidity, with disarming honesty.

They forget that Malaysians of various ethnic groups, urban and rural alike, handed Abdullah Badawi a triumphant success in 2004, with BN winning 90 percent of parliamentary seats and 64 percent of the popular vote.

Indeed, all the seven additional MPs gained by Pakatan in 2013 were delivered by urban Sabahan and Sarawakian voters.

They forget that Malaysians of various ethnic groups, urban and rural alike, handed Abdullah Badawi a triumphant success in 2004, with BN winning 90 percent of parliamentary seats and 64 percent of the popular vote.

Indeed, all the seven additional MPs gained by Pakatan in 2013 were delivered by urban Sabahan and Sarawakian voters.

Still, it is impossible to counteract BN's winning formula in rural seats, if we do not first try to understand it.

One component is undoubtedly poverty, and consequently, constant exposure to our distorted mainstream media. Another factor is an skewed electoral process.

A third is the logistical advantage of BN, using the state civil service facilities for campaigning.

A fourth is the shoddy organisation of Pakatan component parties outside urban areas. And there is a fifth reason: most rural communities live in a pre-industrial era, untouched by the democratic awakening we have have witnessed in urban Malaysia.

Restricted vision in isolated communities

Sarawak and Sabah are crisscrossed by mountain ranges. Most tiny rural communities live in valleys carved by rivers from the rugged landscape.

They practice subsistence farming, and many households earn a monthly income far below the poverty line, RM830 in Sarawak or RM960 in Sabah.

Travelling to a town by river takes days. Even if villagers can scrape together enough cash for a seat on a commercial four-wheel-drive truck, the gravel roads are forbidding.

MASwings

operates a twin-propeller service, once or twice weekly to a handful of

villages, but fares are prohibitive for rural families. Mobile

telephone or internet coverage is extremely sparse.

MASwings

operates a twin-propeller service, once or twice weekly to a handful of

villages, but fares are prohibitive for rural families. Mobile

telephone or internet coverage is extremely sparse.

Political vision is limited by the terrain, and the historical and geographical isolation of these communities.

Big ideas, whether of democracy, good governance, anti-corruption or anti-racism movements, political Islam or liberation theology, 1Malaysia or the welfare state, Marxism or monetarism, have not drifted through these valleys.

Stunted form of democracy

Democracy has not died here. Democracy - as understood by urban Malaysians, including free and fair competition for government, universal suffrage, civil liberties, a system of checks and balance, and an independent press - has not truly been born in rural Sarawak.

Some rural Sarawakians, such as the Iban and the Penan, certainly have an adat or custom of electing their leaders, and a tradition of self-determination, collective decision-making, and egalitarianism.

But Sarawakians from other ethnic groups, including Malays, Bidayuh, Chinese and Orang Ulu, practise feudalism to some degree.

BN has systematically undermined any existing adat of self-determination, by appointing leaders, from the village chief to the penghulu and pemanca or temenggong, and by sacking independent-minded village heads.

BN's patronage has crippled these communities' independence. BN has forged its dacing brand as "apai indai" (parents) to rural communities.

Many rural communities are angered by the loss of their neighbours' land to dams or oil palm estates, but remain afraid to vote against the BN.

BN routinely threatens to deprive them of fuel subsidies, schools, medical care, even disability allowances.

Radio Free Sarawak broadcasts, as well as word of mouth from rural Dayaks and Malays working in towns along the coast or in peninsular Malaysia, have alerted many rural communities to the threats to their NCR land.

Even so, many NCR landowners are as yet unaffected by land grabs, and succumb to the "not in my back yard" sentiment.

They hope that their own land will somehow be spared, by some miracle, from BN's deformed, top-down "development".

Several communities have turned to PKR lawyers to fight for NCR land in court, but ironically, vote for BN in elections.

Many sell their votes readily for small bribes of cash, food or beer. Others are intimidated by BN's threats.

In contrast, urban Malaysians' fear of authority, and of the ethnic "other", is fading fast, thanks to urban class conflict, the Bersih rallies, Pakatan's increasing cohesion, and, ironically, premier Najib's frantic and misguided efforts to use racist invective to save his own skin, ahead of Umno's general assembly this year.

Low incomes, low education, low turnouts

"I am very convinced now that the abject poverty of our natives' folks placed them in a very vulnerable situation, allowing money politics to remain supreme in elections. Rights, idealism and even spiritual principles take a back seat," Sarawak PKR chairperson Baru Bian wrote, after Pakatan failed to win a single rural parliamentary seat on polling day.

"In my area, Limbang, for example, voters were paid RM20, RM30, RM100, RM150, and RM300 depending on the strength of support. Other constituencies were paid RM100 as first payment and RM500 can be claimed after winning the (general election)."

Baru Bian's observation of vote-buying is not simply an old excuse. BN banked heavily on rural votes, and their outlay clearly paid off in GE13.

Gerrymandering has also been honed by BN over decades.

The second smallest parliamentary constituency in Sarawak, Tanjong Manis, has 19,215 registered voters, a quarter of the 84,732 voters in the largest, Stampin (wrested from BN by the DAP with an enormous 18,670 majority).

The smaller rural populations dilute the effects of urban dissent, and make it easier to manipulate and buy voters.

Tanjong Manis had a low turnout of 75 percent. The BN candidate, Norah Abdul Rahman, is chief minister Taib Mahmud's cousin.

Her two sisters, and business partners, had played an unwitting starring role in a recent Global Witness video exposé.

Despite her sisters' shameful insults against rural Sarawakians, Norah won 87 percent of votes cast.

A fourth is the shoddy organisation of Pakatan component parties outside urban areas. And there is a fifth reason: most rural communities live in a pre-industrial era, untouched by the democratic awakening we have have witnessed in urban Malaysia.

Restricted vision in isolated communities

Sarawak and Sabah are crisscrossed by mountain ranges. Most tiny rural communities live in valleys carved by rivers from the rugged landscape.

They practice subsistence farming, and many households earn a monthly income far below the poverty line, RM830 in Sarawak or RM960 in Sabah.

Travelling to a town by river takes days. Even if villagers can scrape together enough cash for a seat on a commercial four-wheel-drive truck, the gravel roads are forbidding.

Political vision is limited by the terrain, and the historical and geographical isolation of these communities.

Big ideas, whether of democracy, good governance, anti-corruption or anti-racism movements, political Islam or liberation theology, 1Malaysia or the welfare state, Marxism or monetarism, have not drifted through these valleys.

Stunted form of democracy

Democracy has not died here. Democracy - as understood by urban Malaysians, including free and fair competition for government, universal suffrage, civil liberties, a system of checks and balance, and an independent press - has not truly been born in rural Sarawak.

Some rural Sarawakians, such as the Iban and the Penan, certainly have an adat or custom of electing their leaders, and a tradition of self-determination, collective decision-making, and egalitarianism.

But Sarawakians from other ethnic groups, including Malays, Bidayuh, Chinese and Orang Ulu, practise feudalism to some degree.

BN has systematically undermined any existing adat of self-determination, by appointing leaders, from the village chief to the penghulu and pemanca or temenggong, and by sacking independent-minded village heads.

BN's patronage has crippled these communities' independence. BN has forged its dacing brand as "apai indai" (parents) to rural communities.

Many rural communities are angered by the loss of their neighbours' land to dams or oil palm estates, but remain afraid to vote against the BN.

BN routinely threatens to deprive them of fuel subsidies, schools, medical care, even disability allowances.

Radio Free Sarawak broadcasts, as well as word of mouth from rural Dayaks and Malays working in towns along the coast or in peninsular Malaysia, have alerted many rural communities to the threats to their NCR land.

Even so, many NCR landowners are as yet unaffected by land grabs, and succumb to the "not in my back yard" sentiment.

They hope that their own land will somehow be spared, by some miracle, from BN's deformed, top-down "development".

Several communities have turned to PKR lawyers to fight for NCR land in court, but ironically, vote for BN in elections.

Many sell their votes readily for small bribes of cash, food or beer. Others are intimidated by BN's threats.

In contrast, urban Malaysians' fear of authority, and of the ethnic "other", is fading fast, thanks to urban class conflict, the Bersih rallies, Pakatan's increasing cohesion, and, ironically, premier Najib's frantic and misguided efforts to use racist invective to save his own skin, ahead of Umno's general assembly this year.

Low incomes, low education, low turnouts

"I am very convinced now that the abject poverty of our natives' folks placed them in a very vulnerable situation, allowing money politics to remain supreme in elections. Rights, idealism and even spiritual principles take a back seat," Sarawak PKR chairperson Baru Bian wrote, after Pakatan failed to win a single rural parliamentary seat on polling day.

"In my area, Limbang, for example, voters were paid RM20, RM30, RM100, RM150, and RM300 depending on the strength of support. Other constituencies were paid RM100 as first payment and RM500 can be claimed after winning the (general election)."

Baru Bian's observation of vote-buying is not simply an old excuse. BN banked heavily on rural votes, and their outlay clearly paid off in GE13.

Gerrymandering has also been honed by BN over decades.

The second smallest parliamentary constituency in Sarawak, Tanjong Manis, has 19,215 registered voters, a quarter of the 84,732 voters in the largest, Stampin (wrested from BN by the DAP with an enormous 18,670 majority).

The smaller rural populations dilute the effects of urban dissent, and make it easier to manipulate and buy voters.

Tanjong Manis had a low turnout of 75 percent. The BN candidate, Norah Abdul Rahman, is chief minister Taib Mahmud's cousin.

Her two sisters, and business partners, had played an unwitting starring role in a recent Global Witness video exposé.

Despite her sisters' shameful insults against rural Sarawakians, Norah won 87 percent of votes cast.

Her victory suggests many of her constituents had never seen the video, thanks to BN's leash on the mainstream media.

The largest constituency, Hulu Rajang, is comparable in size to Pahang, but has only 21,686 names on the roll, and one of the lowest turnout rates nationwide, 68 percent. Low turnouts favour the incumbent.

Lacking supervison, corpses vote?

Baram was expected to go to PKR's Roland Engan. An independent spoiler, Patrick Sibat, after failing in his bid to be PKR candidate, took 363 votes away from PKR. BN's Anyi Ngau squeaked through by a margin of 194. Turnout here, 64 percent, was even lower than Hulu Rajang.

In these enormous constituencies, polls monitors and counting agents are scarce, while voting irregularities are common: cash distribution for votes, electoral roll discrepancies, double voting, and ballot box stuffing.

Intriguingly, there were 351 voters over 90 years old (or 1.87 percent of all voters) in Baram, and 182 (or 1.23 percent) in Hulu Rajang.

These numbers, in closely contested seats, were far higher than the corresponding rates of 0.56 percent in Sarawak overall, 0.77 percent in Sabah, 0.19 percent in Selangor, and 0.23 percent in Pahang.

Did nonagenarians display remarkable stamina in two of the poorest areas in Sabah and Sarawak, two of the poorest states? Or were phantom voters using ICs of deceased voters?

In between elections, BN has been investing little into the impoverished rural communities - keeping them insecure, poor, uneducated and easy to control - while extracting too much from Sarawak's rural populace. BN's rural chokehold is unsustainable.

KERUAH USIT is a

human rights activist - ‘anak Sarawak, bangsa Malaysia’. This weekly

column is an effort to provide a voice for marginalised Malaysians.

Keruah Usit can be contacted at keruah_usit@yahoo.com