A Petronas worker inspects a tanker in Kuala Lumpur

July 3, 2006. — Reuters pics

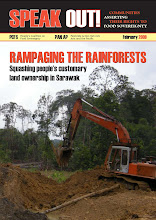

(Comments by Sarawak Headhunter in red).

KUALA

LUMPUR, July 2 — State oil company Petronas is tired of being

Malaysia’s cash trough. Its growing pique at the government flared into

public view here in early June at the World Gas Conference.

If this is how Petronas, which doesn't own any territory from which it exploits the nation's petroleum resources, how does it think Sarawak, Sabah, Kelantan and Terengganu, which own those territories, feel?

They are the nation's real piggy bank, even though they get minimal revenues from their own petroleum resources - and in the case of Kelantan not even a single sen.

UMNO can claim it gives billions of development funds to Kelantan, but the reality is that these funds are spent to benefit cronies and areas that voted for UMNO, leaving the other areas to fend for themselves under an impoverished state government that has been deprived of its rightful petroleum resources.

Chief executive Datuk Shamsul Azhar Abbas took to the stage and

declared that the government’s policy of subsidising fuel was plain

wrong. A murmur ran through the crowd — his boss, Prime Minister Datuk

Seri Najib Razak, was sitting in the front row.

By right, at the very least, the oil and gas producing territories of the nation should enjoy subsidized fuel. Yet they now have the highest number of poor people in the country. There is certainly something wrong here. Who have these so-called subsidies benefited and are they really subsidies?

Moments later, Najib went to the podium himself to remind everybody

that the subsidies — for which Petronas foots the bill — have

“social-economic objectives.”

Petronas must certainly have a certain corporate social responsibility to meet sensible and proper soci0-economic objectives, but certainly not political objectives, as has become the case - transforming Petronas into the political piggy-bank controlled by the Prime Minister and no one else, without any responsibility or accountability, not even to Parliament.

The subtext of that rejoinder: Malaysians pay among the lowest

electricity rates and petrol-pump prices in Asia. While the government

has vowed to “rationalize” that, it is highly unlikely to happen before

elections expected in a few months.

This is certainly not true and must be seen in the overall context of consumer prices generally. Any purported "rationalization" would result in further distortion of an economy already burdened by leakages due to corruption, mismanagement, extravagance, bloated project pricing, plain looting, pre-election largesse and bribery and many other fiscal scandals that have drained the economy but have been covered by petroleum revenues.

The polite but pointed disagreement was the latest sign of

assertiveness from an oil company that prime ministers have treated as a

piggy bank for pet projects since it was established in 1974.

Interviews with current and former officials, and an examination of

Petronas and government documents show that strains have been building

behind the scenes over how much money the company hands over to the

government in the form of fuel subsidies, dividends and taxes.

Financial data reviewed by Reuters show the government has

increasingly relied on Petronas’s payments — a “dividend” to its sole

shareholder — to plug fiscal deficits that have begun to alarm ratings

agencies and analysts.

The data also show these payments grew over the past several years as

oil prices soared, along with government spending. But Malaysia’s

official accounts do not show how the money is being spent — and the

government has steadfastly refused to disclose any details about that.

The government in particular the Prime Ministers past and present are obviously not going to disclose just how irresponsible they have been with the nation's petroleum revenues coughed up by Petronas.

“We need cash”

Shamsul delivers his address during the World Gas Conference 2012 in Kuala Lumpur June 4, 2012.

Petronas

is Malaysia’s largest single taxpayer and biggest source of revenue,

covering as much as 45 per cent of the government’s budget. Unlike other

oil-rich nations such as Saudi Arabia, Norway or Brazil, Malaysia runs

chronic, large budget deficits that have expanded even as oil revenues

increased. Last year’s fiscal gap, at 5 per cent of gross domestic

product, trailed only India’s for the dubious distinction of biggest in

emerging Asia, and it may widen this year.

Subsidies account for a big chunk of the deficit. They have other

downsides as well, Shamsul noted in his speech to the gas conference.

“Subsidies distort transparency, reduce competition and deter new

investments,” he said, adding that Petronas paid between RM18 billion

and RM20 billion a year to subsidize gas consumption.

Why should Petronas pay to subsidize gas consumption and who benefits from these "subsidies", directly or indirectly? Could the chief beneficiaries in fact be the crony-run IPPs? Yet electricity consumers are facing threats of higher "costs". Is Petronas being forced to subsidize inefficiency of and profiteering by UMNO's cronies?

Malaysia is not facing a fiscal crisis. Foreign investors eagerly buy

Malaysian government bonds, confident the country’s reserves of oil,

gas and foreign currency are deep enough to ensure the debt will be

repaid.

That faith will be tested over the next few months.

Falling oil and gas prices will likely constrain Petronas’s 2012

profits, and a worsening euro-zone crisis may hurt the country’s

exports. Smaller Petronas payouts and slowing economic growth would

pinch government finances.

Shamsul argues now is an opportune time to pursue foreign

acquisitions on the cheap as Malaysia’s domestic energy supplies

deplete. On Thursday, the company announced it was acquiring its

Canadian joint-venture partner, Progress Energy Resources Corp, for

US$4.7 billion (RM14.1 billion). More may be in the offing.

“Mind you, for that to happen, we need cash,” Shamsul said in his speech.

The trouble is, the government needs the cash, too.

People walk outside the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, September 12, 2001

Towers over Malaysia

Petronas, Malaysia’s only global Fortune 500 company, towers over the

country — literally and figuratively. Its 88-storey twin towers, once

the world’s tallest buildings, dominate the skyline of Kuala Lumpur.

Petronas’s oil and gas reserves rank 28th in the world, according to

data from PetroStrategies in Plano, Texas, ahead of some better known

players such as Norway’s Statoil and CNOOC, China National Offshore Oil

Corp.

Unusual for a state-owned enterprise, Petronas’s debt is rated

stronger than the sovereign state’s. The company had about US$15.6

billion in total borrowing as of March 31 and counts U.S. insurer Aflac

Inc among the debt holders.

Petronas’ CEO and board, however, serve at the pleasure of the prime

minister. Over the years, prime ministers have tapped into Petronas

funds to build their dream projects and bail out their mistakes.

Political leaders were used to dealing with yes-men in the company,

which on Malaysia’s organisation chart is part of the prime minister’s

office.

Now Petronas is trying to say no.

UMNO and the present Prime Minister aren't going to like that, since that could put a spanner in the UMNO works and plans especially for the coming 13th general elections that they hope to steal.

Like all state-owned oil companies, Petronas is expected to pass

along a share of profit to the government, just as a private sector oil

company pays dividends to shareholders.

Those dividends gobbled up almost 55 per cent of its net profits in

the fiscal year ended March 31, 2011, well above the average of 38 per

cent paid by national oil companies around the world, Petronas figures

show.

Only sheer greed and a "couldn't care less" attitude about prudent management can account for this.

Including taxes, export duties and the dividend, Petronas estimates

its total payments to the Malaysian government added up to RM65.7

billion in that fiscal year.

Swelling deficit

Najib would be forced to cut spending if he did not have access to Petronas funds.

Petronas

has been pushing for a new dividend policy that would set the annual

payout to the government at 30 per cent of profits instead of the flat

RM28 billion it will pay this year.

A lower payout would preserve money to reinvest in global oil and gas

exploration in order to compensate for declining domestic supplies.

A Reuters analysis of Petronas and government financial data shows

Petronas would have paid close to RM17 billion in the March 2011 fiscal

year if the 30 per cent dividend formula was in place.

A smaller dividend payment would have deepened Malaysia’s fiscal

deficit, swelling it to about 6.5 per cent of gross domestic product.

That is nearly triple the average among the world’s emerging-market

economies, according to International Monetary Fund data.

With less Petronas money under the new formula, Prime Minister Najib

would have three unpopular options: cutting spending, increasing taxes

or ramping up the deficit. Worsening public finances could unsettle

foreign investors, who hold about 39 per cent of the government’s local

currency debt, the highest share in emerging Asia.

The Petronas CEO put a brave face on it when Reuters asked him if the

new formula might be put in place this year, with elections now

expected as soon as September.

“The government is fairly aware of Petronas’s need to have our own

funding for growth,” Shamsul said after the company released financial

results on May 31. “They respect that and they will agree to our

request.”

Since when did the UMNO/BN government respect anything other than what they and their cronies want?

Najib’s office declined to comment.

Respectfully?

Election stimulus?

Najib, who took over mid-term from his predecessor and has yet to

receive an electoral mandate as prime minister, can ill-afford to

accommodate Petronas right now on the dividend. He has raised

civil-servant wages and approved cash payouts to low-income households —

vote-winning measures paid for in part by Petronas.

In reality paid for by Sarawak, Sabah, Kelantan and Terengganu.

Ratings agency Fitch warned in February that Malaysia’s budget was

too reliant on petroleum receipts, and elections could drive up spending

and deepen the budget deficit.

“If aggressive stimulus measures were implemented and this led to a

sustained increase in public debt ratios, it would be negative for the

ratings,” Fitch wrote.

That may already be happening. The government in June asked

parliament to approve another RM13.8 billion in supplementary spending —

more than half of it for food and fuel subsidies — which would swell

the fiscal deficit to 6 per cent of GDP.

Petronas only began detailing its contributions to the government two

years ago — around the time it began lobbying for a change in the

dividend policy. Indeed, the word “dividend” does not even appear in its

annual reports for 2001 through 2009.

Reuters has filled in some of the gaps from previous years, obtaining

figures from former prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, now adviser

to the oil company, dating back to 1976. Petronas declined to confirm

their accuracy.

No public disclosure

Dr Mahathir’s data show Petronas payments to the state more than

doubled between 2005 and 2011 as oil prices soared. Malaysia’s spending

swelled, too, widening the budget deficit even though revenues rose. But

Malaysia would not disclose what the Petronas money is being spent on.

Reuters placed an official request for that data from Malaysia’s

accountant general’s office, but the audit agency said it could provide

budgetary figures for everything except Petronas’s contributions.

Without access to official figures, it is difficult to determine how

the government spends Petronas money. Dr Mahathir told Reuters he

released additional Petronas data on his blog as an “appeal” for more

clarity on where the money went after he stepped down from office in

2003.

The bulk of it appears to be going into operating expenses, including

higher wages for the more than 1.4 million civil servants who are

mostly Malays, Dr Mahathir said.

Since Najib took office in 2009, operating expenses have risen by

almost 16 per cent. Development spending, which includes education,

security and healthcare, has stayed flat.

Increased wages are a recurring cost, Dr Mahathir pointed out in an

interview from his office on the 83rd floor of the Petronas Towers. Once

pay goes up, he said, it is difficult to cut in lean years.

“So the result is, you take more from development expenditure because

development expenditure is not a statutory requirement,” he said. “You

can cut.”

Not a word about the development and maintenance costs of Putrajaya. Who knows what these are and what kind of a burden they have become to the government. Indeed, even a new government would find itself grossly over-burdened, the extent of which is something the present government is desperately trying to hide.

Other than the other undesirable legacies Mahathir @ Dr Malignant has left the nation, this would also be an enduring burden upon the country that nothing that comes out of a non-revenue generating Putrajaya and its over-paid and highly bloated Malay-stuffed civil service can ever justify.

Dr Mahathir smiles in his office at the top of the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur November 2, 2004.

Expanding abroad

As domestic oil supplies shrink, Petronas has been expanding abroad,

investing in Sudanese oil, South African petrol stations and European

liquefied natural gas. Its corporate operations map shows a presence on

five continents.

But 29 per cent of the company’s international production is

concentrated in Sudan and South Sudan, and clashes along their border

have virtually shut down most of the pipelines. Shamsul warned that a

halt in Sudan production would cost the company RM3 billion.

That is one reason behind the planned purchase of Canada’s Progress

Energy. Shamsul said Thursday that the deal would boost the company’s

gas resources in “a geopolitically stable region.”

Deals like this take money, and Petronas argues it cannot fulfil its

mission when it is handing over more than half its profits to the

government.

Petronas board member Mohammed Azhar Osman Khairuddin told

unidentified US diplomats that the oil company “feels tremendous

pressure to grow its business in order to maintain Malaysia’s political

status.”

That is to say keep a totally and irredeemably corrupt and mismanaged UMNO/BN regime in place. What a complete waste of Petronas revenues contributed to the UMNO/BN government.

Azhar said Petronas wanted the money invested in oil and gas assets

“to promote future profitability rather than be spent now on domestic

programmes for political gain”, according to a diplomatic cable released

by Wikileaks in June of last year.

Neither Azhar nor Petronas responded to requests for comment.

How can they defy the nation's CEO, the Prime Minister, who has already embarked upon laying waste to Felda?

The tug-of-war between government payments and corporate investments is a sore point with other oil companies as well.

Petronas faces a milder version of the dilemma facing Mexico’s

national oil company, Pemex. The Mexican government is extracting so

much cash from the business that Pemex is having trouble investing in

production — and output has waned. Fitch assigned a “BBB” rating to the

oil company’s latest debt issuance, citing a substantial tax burden and

“exposure to political interference risk.”

With global energy demand expected to rise by around 30 per cent by

2050 as the population rises to 9 billion, oil executives are asking

whether governments are a major obstacle to ensuring future supplies at

affordable levels.

Exxon Mobil Chief Executive Rex Tillerson told the World Gas

Conference that regulation, taxes and subsidies are placing at risk the

projects needed to fuel global growth. If the situation persists,

governments will find their economies “walking backwards,” he said.

Petronas has four oil projects in Iraq, which are expected to achieve

commercial production this year. Shamsul estimates that Petronas’s

share of Iraqi output will peak at 800,000 barrels of oil per day by

2015 — about 45 per cent more than Malaysia’s annual crude oil

production.

The company has not disclosed how much it is investing in Iraq, but

as much as US$8 billion is going into one field alone, Gharf Oilfield,

which Petronas is developing along with Japan Petroleum Exploration Co.

“The reason (Petronas) does not want to give money to the government

is because it needs the money to reinvest,” Dr Mahathir said. “This is a

very costly business as you know. Everything runs into the billions of

dollars.”

Mahathir of course is shy to mention how costly his running of Malaysia has been and will continue to be, even though he is no longer Prime Minister.

Najib (right) talks to Hassan as they arrive for the opening of 14th Asia Oil & Gas Conference in Kuala Lumpur June 8, 2009.

Good governance

As state oil companies go, Petronas has a good reputation for

governance. A 2011 World Bank working paper on governance and

performance of national oil companies ranked Petronas slightly above the

global average.

But it has been called upon to bankroll some questionable projects,

both under Najib and his predecessors. Twice — in 1984 and 1989 — Dr

Mahathir asked Petronas to bail out scandal-ridden Bank Bumiputra Bhd

from collapse. In those two rescues, Petronas injected a total of RM3.3

billion into the bank.

The only reason for Bank Bumiputra needing to be bailed out twice can be traced to the shenanigans perpetrated by UMNO's own cronies as well as its own deliberate refusal to pay its own debts incurred for the UMNO PWTC HQ and owing to the bank.

These have presumably been written off by Bank Bumiputra which conveniently also no longer exists.

UMNO has thus been in possession and occupation of its PWTC HQ free of charge courtesy of Petronas and the petroleum revenues of Sarawak, Sabah, Kelantan and Terengganu.

Dr Mahathir drew criticism for tapping Petronas to bail out a

debt-burdened shipping concern controlled by his eldest son, Mirzan, and

again to support auto company Proton, which makes the Lotus Formula One

car.

Dr Mahathir denied he had bailed out his son. Petronas “drove a very

hard bargain” and ended up turning a profit on the deal, he insisted.

Petronas has repeatedly declined to discuss the bailouts.

Easy for Mahathir to say, but where's the proof that Petronas made a profit from the deal?

The strains between Petronas and the government spilled out into the public after Najib took office in 2009.

Tan Sri Hassan Marican, Petronas’s CEO at the time, disagreed with

Najib over issues ranging from who should be named to the Petronas board

to which Formula One car to sponsor.

Reuters has learned that Najib gave Hassan just six days’ notice that

his contract would not be renewed in 2010, ending a 21-year career.

Three people with direct knowledge of the situation said Hassan was let

go because he did not get along with Najib.

“Six days to pack up a career spanning more than two decades,” said a person close to Hassan.

Hassan, now a board member at US oil major ConocoPhillips and

chairman of utilities company Singapore Power, did not respond to

repeated interview requests.

Appointed by Dr Mahathir, the 59-year-old accountant by training had

considerable freedom before the clashes with Najib. Dr Mahathir said

Hassan often said “no” to his suggestions, though he did agree to bail

out the national car company that was the prime minister’s pride and joy

and the company owned by Dr Mahathir’s son.

In the whole history of Mahathir's government, who from the establishment ever dared to say "no" to him and survived to tell the tale?

Hassan refused to use inexperienced Malaysian companies to develop

Malaysia’s oil and gas industry, or to pursue costly ventures to develop

the country’s marginal oil fields, the source close to Hassan said.

Those two projects are now part of Najib’s ambitious US$444 billion

economic transformation programme launched in September 2010 — just

seven months after Hassan’s removal. — Reuters

For the sake of not just Petronas, but the nation as a whole, it should be obvious to all right-thinking Malaysians that UMNO/BN's unholy reign of corruption, extravagance and mismanagement MUST come to an end in the coming GE-13 - Sarawak Headhunter