SNAP: WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO

By Paul Kadang, Director of Operations, Sarawak National Party (SNAP)

SNAP’s recent re-emergence to reclaim its place in the Sarawak political arena has sparked numerous allegations and prejudgements on the motives of the prime movers of the party’s re-vitalisation. Presumably made with good intentions, these prejudgements have been voiced out in the internet by political observers who seem to hold themselves out as being totally familiar with the present Sarawak political scene. Most of these, however, contain presumptions that have not been thoroughly examined.

Let me elaborate on the reasons and circumstances leading to SNAP’s re-emergence.

Background

From the beginning since its founding in 1961, SNAP has had two important characteristics vis-a-vis its support: it has always been a multiracial party. Of equal importance has been its emphasis on Dayak interests, which is not surprising since this community forms its inner core.

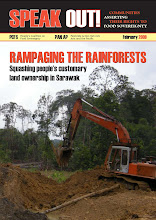

It had been the tearing and cracking of this core by its political opponents since 1970, through their divide and rule policies, which not only decapitated SNAP as a viable political organization but also formed the first significant break in Dayak communal unity. The manifestation of these divide and rule policies has continued to this day and has been a contributing factor to the dispossession of the Dayak people of much of their properties and lands by unscrupulous people.

Since that time the holy grail of Dayak politics has been to forge their internal unity and cohesion in their search for equitable power sharing in the country. They have laboured hard towards this end but so far without success. And so to this day, Dayaks have continued to be splintered and their political representation fragmented amongst the various parties in Sarawak.

Over the past eight years, Ibans and other natives did not have any indigenous political party as their platform for democratic dissent. They gave the benefit of the doubt to SPDP and PRS and even PBB to try to regain the rightful political significance of the native population. In those eight years, the blatant disregard for Native Customary Rights and Native Customary Land as enshrined in the laws of the state, continued and became even more widespread till today. All these happened without even the slightest protest coming from legislators and political parties that claim to represent, protect and uphold native interests be they the PBB, SPDP or PRS.

By 2008, the natives, particularly those from the Dayak communities, were totally marginalised politically. A new generation of native intellectuals then decided that the time had come for natives to depend on no one but themselves to fight their battles.

Answering the clarion call of Reformasi that have yielded fruits in the federal general elections of March 2008, these Dayak intellectuals began to look at PKR as the platform from which to fight their battles. Some became PKR members, while some others watched with keen interest and gave their support from the fringes.

But two years later, they slowly drifted away from PKR for reasons which in total had shown to these intellectuals that native problems are of a low priority to PKR. The instances are as follows.

PKR’s Relationship with Natives and Native Issues

The records show that PKR in Sarawak was started by disenchanted Malay-Melanau politicians splintered from the then and present ruling elite. For ten years the main issues that made up PKR Sarawak’s political agenda were their typical infighting and their urge to find a way to replace Taib Mahmud and gang as the ruling elite of Sarawak. All the office-bearers and head of PKR Sarawak were from that group for most of the twelve years of PKR Sarawak’s existence.

It was only in 2008, with the entry of other native and Dayak intellectuals into the party that wider native issues became part of PKR’s campaign fodder to attract these native votes. Before this, there were almost no PKR divisions in Dayak-majority constituencies. Attempts were then made by personalities like Nicholas Bawin to open up branches in Dayak native-majority constituencies.

It is notable that only after twelve years, for the first time ever, a Dayak was appointed a few months ago as head of PKR Sarawak. Even then the appointment was not without vociferous protests from the pioneers of PKR Sarawak. Till now, no Iban sits in PKR’s inflated Majlis Pimpinan Pusat or its political bureau. These are ominous signs of the patronising attitude of PKR that culminated in the Batang Ai by-election catastrophe of April 2009.

The Batang Ai By-Election

The native intellectuals group, Malay Melanau and Dayak, that supported PKR had by the end of 2008 quadrupled in number, ready to adopt PKR as the saviour of the natives. Then came the Batang Ai by-election and it was clear to most of PKR Sarawak native leaders that Nicholas Bawin was the most viable PKR candidate and was expected to be nominated. They were astonished therefore that a long time ex-yang berhormat, formerly from the ruling coalition who was not known to be associated with PKR, was appointed instead of Bawin. That was at the behest and financial lobbying of a Chinese towkay whose official affiliation with PKR was nil but who evidently held a major sway in the personal considerations of PKR’s Ketua Umum. Without consultation with PKR’s native leaders, Bawin was dropped. Such is ‘democracy’ in PKR.

The result of the by-election, as expected, was a major disaster to PKR’s attempts to make inroads into Sarawak Dayak native politics. PKR’s candidate was thrashed. He obviously did not enjoy the confidence of these intellectuals, who chose to stay away in protest against the evident highhandedness. As an excuse for their defeat, PKR went into its typical damage control mode in alleging, for instance, that the ballot boxes were switched while in helicopters. That’s just vintage PKR to ignore the elephant in the room.

In the post-mortem, if ever really there was one, the issue of Dayak leaders’ lack of influence in PKR’s decision-making in Sarawak was never even addressed. Batang Ai is one of the many things observed by these intellectuals which raised questions about native-issue priorities in PKR. They have since kept their distance from the party. PKR remains in their mind as a party that will perpetuate neo-colonial intentions in Sarawak. This is obvious for those who care to see.

Consequently, while those intellectuals were grappling to find a vehicle to voice out native dissatisfaction by natives themselves, SNAP’s re-registration was ordered by the courts. It is only natural therefore that SNAP became a magnet to these partyless native opposition leaders.

SARAWAK STATE ELECTIONS 2011

SNAP was and is very much in favour of an opposition electoral pact for obvious reasons. Now that the possibility of such a pact appears to be diminishing by the day, it is important that political observers and commentators are made aware of the following:

Negotiations

The opposition grouping has no chairman nor a fixed structure. Even then, it does not matter much to SNAP as to who takes the lead in convening negotiations between the four opposition parties (SNAP, PKR, DAP and PAS) as long as certain rules of political decency and civil negotiations are followed and that the management of the negotiations by whomsoever has the competency and the power to decide.

PKR took the mantle and in the same breath publicly announced that it will run in 53 seats and SNAP will be accorded only 3. It was as if the seats were for PKR to distribute. SNAP had no choice but to respond publicly that it intends to run in all of the native-majority seats numbering 29.

Negotiations commenced in a haphazard manner and much later than ideally possible. SNAP refuses to be marginalised and to underscore its seriousness and capacity to compete, declared publicly its 16 candidates for 16 named constituencies. A startled PKR came back to ‘offer’ 4 seats, instead of 3. SNAP responded to this infantile insult by announcing 11 more candidates for 11 more constituencies. Altogether totalling 27 seats.

PKR’s incompetency in leadership and management of the negotiations was obvious. There was no negotiation agenda and things were done by the seat of their pants and at their convenience. SNAP expected the first session would have been attended by decision-makers of all parties. There is no point in negotiating if the negotiators have no power or mandate to decide. Decisions from higher-ups must be obtained at the point of negotiation. That wasn’t the case with PKR. At all times, PKR insisted that the final decision would be made by KL after a negotiating position had been reached by the parties. To any seasoned negotiator, such a statement is already a ball-breaker.

We had also expected that the first order of the day was to get a consensus of the proportionate spread of the number of seats to be contested by each party in accordance to macro demographic factors which all four parties hold themselves to champion for. It was clear that DAP would run in Chinese-majority areas, PAS in a few Muslim-majority areas and PKR in Malay-Melanau areas, where they had concentrated their efforts in the past decade for better or for worse. SNAP, being a multiracial party but traditionally a Dayak-based one, will contest in the native-majority areas. It was only in the mixed areas that overlapping claims will have to be resolved through negotiations.

But PKR having suddenly realised that native issues could be the determining issues in the coming elections, and still hung-over from the ecstasy of the 2008 electoral tsunami in the peninsular, thought that by placing their candidates in these native constituencies PKR can be the beneficiary of a Sarawak tsunami.

The opinion-makers and intellectuals who had fled to SNAP therefore fear that the beneficiary of native electoral dissatisfaction may be a national party that has shown in the last two years little sensitivity to the natives’ political predicament. They fear that Sarawak’s native problems, under PKR, will remain secondary to a grander federal plan of PKR’s national leaders. At worst, SNAP will never be able to be given back those constituencies by PKR.

If in fact PKR had made a positive impact in native constituencies and indeed enjoyed native support, by putting in hard work in building up an articulation of native dissatisfaction, the results would have been evident. But instead, PKR had never won nor come close to winning a native-majority seat in 3 federal elections and 2 state elections in the 12 years of their existence in Sarawak. In fact, a number of their candidates lost their deposits. So much for PKR’s desire to contest in 53 seats.

The second order of the day would be for the negotiating parties to consider the ‘winnability’ of their candidates as a basis for their allocation of the overlapping seats. Till this very moment, the ‘conductor’ of the negotiations themselves has not sorted out their own internal selection problems as to who runs where. They fear that if they make representations of the winnability of a particular candidate, it may incur the wrath of another party member also aspiring to be the candidate for the same area.

Out of this fear and indiscipline, it is PKR’s practice that their candidates list is only completed on the eve of nomination day so that those among their members who have lost out will not have options but to play along. Knowing this, SNAP decided that it would not be encumbered by PKR’s internal deficiencies. SNAP announced its candidates way ahead of time to give them a head start in going to the ground in the vast constituencies to familiarise the voters with their candidacy.

What is the Status Quo?

To date, SNAP has announced its decision to run in 27 of the 29 native-majority seats. It has refrained from contesting in the remaining 2 seats in deference to the work done by and its support for two PKR native leaders. In a gesture of goodwill and in recognition of the winnability factor, these concessions are made. The truth is that PKR has no other native leaders of their calibre and SNAP’s candidates in the 27 seats will be at par, if not better than PKR’s candidates.

As it has always maintained, SNAP will be happy to be a part of an electoral pact if it is allowed to contest in the said 27 constituencies. However, should there be a free for all, SNAP has the capacity and candidates to contest up to 40 seats. That is an option that it will take only if there is no more rules of engagement among the opposition parties.

Finances

Opposition supporters are hoping, and SNAP along with them, that the natives in a bold decisive move will act with political maturity and courage to invoke an electoral tsunami. It is indeed high expectations.

However, it is disheartening to note that while such a lofty commitment is expected of natives, the possibility that their commitment might extend to financing the election campaign that they favour is strangely dismissed by these commentators. On this premise, SNAP is maliciously accused of conspiring with BN in order to get political funding. Such accusations are insulting to SNAP and are the furthest from the truth.

These commentators underestimated and underrated successful natives as people who cannot put money where their hearts are. In the last few months, SNAP has been inundated with monetary contributions from well-to-do natives working abroad. Perhaps these commentators have stereotyped natives to the point that it is unthinkable to them, for example, that a native petroleum engineer working in the Middle East and earning US$ 25,000 a month and who is moved by the plight of his community, will contribute up to RM100,000 to SNAP’s election campaign.

SNAP needs money badly but it also realises that an efficient and honest campaign will not be too dependent on huge campaign budgets.

Quality of Candidates

It has been mentioned that SNAP’s candidates are of the quality that can be bought over once elected. It is as if there is a fail-proof formula to prevent this. At SNAP, we humbly submit that we have dealt with this issue on a ‘best-effort’ basis. It is only those who have not gone through the rigours of election management that wishfully think a watertight formula is ever possible. By the same token SNAP would like to hear those people who doubt the integrity of our candidates, if it is at all possible, to attest their supreme confidence that candidates of PKR or any of the other opposition parties will not jump ship once elected.

SNAP’s list of candidates is multiracial in nature. It comprises young professionals and also a good mix of Dayak nationalists with experience far beyond those of the commentators.

Conclusion

Let the voters decide. SNAP respects the opinions of others as their right to voice out opinions in a democracy. By the same token, SNAP reserves its right to its own political action without having to be accused of treachery and all the other tales that make interesting gossip at the teh tarek stalls.

SNAP urges that before certain presumptions are made, basic empirical research should be done that goes beyond mere rhetoric and wishful thinking.

Like everybody else in this state, we wish to unseat the Taib regime. But we will do it in a manner that safeguards Sarawakian and Dayak control over their own affairs and destiny, and avoid jumping out of the pot into the fire. Our words are based on actual experience but we certainly welcome learned comments and guidance from armchair politicians made in good faith.

God bless the people of Sarawak.

---

The writer holds a master degree in political science from University of British Columbia, Canada. He was previously the deputy secretary-general of PKR and is now the director of elections for SNAP in the coming Sarawak state elections.

SARAWAK NATIONAL PARTY (SNAP)Parti Asal Bansa Sarawak

SNAP Headquarters, Rubber Road,

93400 Kuching, Sarawak.

phone: +6082 230 659 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +6082 230 659 end_of_the_skype_highlighting

e-mail: sarawaknationalparty@gmail.com