By Bunga Pakma

On 16 September 1963, all the elements were in place for the unfolding of a political story which, whatever its outcome would be, was certain to go through strange and wrenching twists of plot. Some of these elements were clear to see, others hidden.

It must have crossed many observers’ minds that the component states that made up this new “Malaysia” were an odd quartet. Malaya was a patchwork of small states, most of them feudal régimes headed by Malay kinglets. Singapore was a commercial city-state, predominantly Chinese with a strong British cast, but wholly business. Sarawak—Britain’s last pukka colony—had been ruled by a white family for 100 years, and Sabah had emerged from the strange position of being run by a Limited Company.

Each partner-to-be in the Malaysian enterprise joined with vastly differing experiences and expectations. The only thing they had in common was that each territory was home to a bewildering variety of peoples, languages and cultures, and none of these people had ever known anything except authoritarian rule. Upon what did they believe they were to agree?

As we have seen, Malaysia was a marriage of convenience, particularly for the convenience of the Malayan élite and the British. Love had no place in the arrangement, and inevitably members would be fighting as to who “wore the pants” in the foursome. KL took a traditional Islamic view of the federation. KL was the husband, and he took three wives. Singapore disputed KL’s position and demanded to be treated as an equal partner. KL booted Singapore out of Malaysia.

That left Semenanjung and Sabah and Sarawak. KL was hardly as noble as D’Artagnan, and the principle that governed Federal/East M’sian relations was not “One for all and all for one.” The mere notion of treating others as equal partners is as repugnant to the Malay élite as a ham sandwich.

My main source for today’s piece is Michael Leigh’s The Rising Moon: Political Change in Sarawak, published by Sydney University Press 1974. Much has happened since then, but Leigh’s study remains quite fresh. The pattern of Sarawak/Semenanjung relations Leigh demonstrates at the very beginning of Malaysia remains intact today.

The Peninsular élite—and that includes the Tunku—may not have consciously thought the word “colonize” in connection with Sarawak, but their actions declared that this was their aim. Sarawak’s first chief minister, Stephen Kalong Ningkan, explicitly voiced his concerns at Peninsular neo-colonialism. Ningkan was a Sarawak patriot and a tough fighter. He had most Sarawakians behind him. Alas, he was nourishing a viper in his bosom.

A young Melanau man named Abdul Taib bin Mahmud had taken a degree in Law at the University of Adelaide in 1960 and was thus one of the very few natives qualified for government service. He, together with his uncle Abdul Rahman bin Ya’kub, was a founder-member of the party Barisan Ra’ayat Jati Sarawak. Leigh comments:

“…[BARJASA] served to underline and help perpetuate the most basic cleavage within the Malay community, one which had disrupted personal relationships from the time of Cession. The chairman… the highest ranking Sibu Malay…had clashed bitterly with the Datu Bandar…” (30)

BARJASA, then, was created to further personal jealousies and ambitions, not issues. BARJASA was a component of the Alliance (modeled on that of Malaya) formed in 1962. BARJASA had close ties with and received much support from their Peninsular counterparts.

Taib did not stand for election next year. Nonetheless, his party won 20% of seats in the Council Negri and he was appointed to the first cabinet as Minister of Communications and Works. His uncle Ya’kub (sic) went to KL as Deputy Minister and worked directly with Razak.

Ningkan faced crisis after crisis in his few years as chief minister. The Tunku had no patience with Ningkan’s insistence on Sarawak’s states rights (including the retention of English), and was irritated by the squabbling among Sarawak Malay leaders.

There is a gap in the narrative as Leigh tells it. In June 1966 twenty-one Alliance members of the Council Negri signed a petition stating they had lost confidence in Kalong Ningkan and demanded his removal. This was presented to the Tunku, and the Tunku dismissed Ningkan.

Ningkan, says Leigh, believed that his accusers had been flown to KL in order to sign the paper there. What is left unclear to me is: 1) What was the efficient cause for such a drastic step? (I say “drastic” because a vote of no confidence must constitutionally be put to the Council in session; a piece of paper is not a vote.) 2) Who organized the petition? Leigh implies that Taib was the man who brought these signatures to the Tunku (105). Can we infer that Taib was the principle mover behind the plot to oust Ningkan?

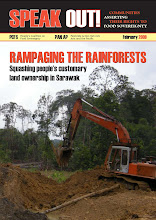

With plenty of help from KL, a new Sarawak government was formed under Tawi Sli, Dayak, but a more compliant fellow, in July. Taib promptly created a new ministry for himself. This new Ministry of Development and Forestry “cut across the lines of responsibility in a number of departments,” in other words, Taib could make decisions on his own without consulting any other ministry. That’s power.

The Supreme Court declared Ningkan’s dismissal unconstitutional. Acting PM Razak rushed to Kuching and tried to arrange a quick no-confidence vote. Ningkan managed to block that, so Razak declared a state of emergency. My, how easy. Then Razak changed the Federal constitution, and sacked Ningkan for good. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Ya’kub and Taib rebranded themselves as Party Bumiputra in 1968. Voting in the General Election started 10 May 1969, and we all know what happened then. Parliamentary democracy was cancelled for a year. Elections were re-run in June 1970. Early next month PM Razak flew to Kuching and cut a deal that put Ya’kub (sic) in as Chief Minister.

So this Melanau family at last succeeded in founding a dynasty. After this Accession, nothing has changed politically for forty years. In 1981 the CM changed. We did note that some unpleasantness was taking place in the family.

As Gibbon says, history is the record of the “crimes, follies, and disasters of mankind.” Let me recap the lessons of Sarawak history as I see them under these three heads.

The signal disasters Sarawak suffered in the 20th century were two. A weak, irresponsible, unimaginative and vain rajah came to power. He neglected to care for what was entrusted to him and he refused to let anyone take up that trust. Then when the Japanese were defeated, Sarawak became the spoils of an imperialistic power. Her fate was taken from her hands, and Sarawak became a little piece in the great, big important game of the Cold War.

Things without number come under the class of follies. If the British thought they were establishing democracy here, they were quite mistaken. The British could never quit the habits of behaving as if superior, of ordering people around and wanting to have everything their

way.They rushed out of Sarawak in unseemly haste after having prepared a régime that would stay attached to British interests (i.e. not Communist), but with no clear plan for the welfare of Sarawak’s people. George Bush is a recent example of the same unconcern.

The Brits essentially left Sarawak naked and defenseless against the first opportunist to come along. So now we consider crimes. That first opportunist was Malaya. The Malay élite feels only contempt for Others (especially brown people who are not Muslims) and they reasoned that Sarawak’s resources should go to real human beings who deserve them.

It was not going to be easy for KL to colonize Sarawak without a partner in crime, an insider. Ya’kub (sic) and Taib presented themselves at the first opportunity. From a young age Taib shaped his career to one end, the acquisition of absolute authority over Sarawak and its resources. Unlike many cunning men, he achieved his plan. In the devil’s arts of creating and using division, distrust, hate, and greed, he is a master. As for the art of deception, I don’t know. Many of us have smelled him from long ago, and didn’t like what they smellt, but Taib certainly can gull a mark. In the process Taib has beggared us, destroyed many, many lives and rendered this beautiful state a waste land.

See also:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3 and

Part 4.