AND PROTECTING INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS

Public Forum on Sustainable Palm Oil

6 January 2005, Kuala Lumpur

Summary of presentation by

COLIN NICHOLAS

Coordinator

Center for Orang Asli Concerns

Peoples and numbers

The indigenous peoples of Malaysia are not a homogenous group. In Peninsular Malaysia, they are distributed culturally and linguistically among 19 distinct ethnic groups (e.g. Semai, Jakun, Temiar, Mah Meri and Orang Kanaq) and are collectively called Orang Asli. They number 145,000 today i.e. only 0.5 per cent of the national population.

The indigenous peoples of Malaysia are not a homogenous group. In Peninsular Malaysia, they are distributed culturally and linguistically among 19 distinct ethnic groups (e.g. Semai, Jakun, Temiar, Mah Meri and Orang Kanaq) and are collectively called Orang Asli. They number 145,000 today i.e. only 0.5 per cent of the national population.In Sabah, the indigenous communities are a majority in the state, making up 85 per cent of the state population of 2 million. The 39 ethnic groups – including Kadazan, Dusun, Murut, Paitan and Bajau – are collectively referred to as Anak Negeri or natives of the state.

In Sarawak, the indigenous groups, now commonly referred to collectively as Dayak and Orang Ulu, account for 44 per cent of the state population of 2.2 million. The Dayak groups include the Iban, Melanau and Bidayuh while Orang Ulu groups include the Penan, Ukit, and Kenyah.

Collectively, all the indigenous peoples in these three regions are referred to as Orang Asal.

Land and indigenous peoples

First, it is important to appreciate that the one distinctive feature that differentiates indigenous peoples from others is their special attachment to their traditional territories. In fact, Orang Asal survival and identity as a people is very much linked to the specific ecological niche that they call their nenggirik, adat land or native customary land. The elements of Orang Asal identity – their spirituality, their customs, their culture, their traditions and their worldview – owe its conceptualisation to the Orang Asal’s attachment to this particular territory. Consequently, any change in the nature and extent of the traditional territory (whether through its physical ruin or whether the Orang Asal are involuntarily relocated away from it) will have significant impact on their identity and survival as a people.

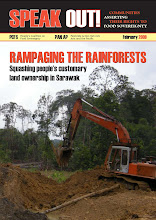

The threats to Orang Asal lands today come from a variety of sources: development projects (such as dams, highways, golf courses, universities and housing projects) as well as from logging and agricultural expansion schemes. Invariably it is frequently businesses that encroach on, and often appropriate, indigenous traditional territories on a large scale. The Sarawak government, for example, recently revealed that as of 1st December 2004, 38 forest plantation licences covering a total of 2.4 million hectares had been issued. And most of the areas are lands claimed by the native peoples there.

Repeatedly, these encroachments and appropriations often result in conflicts between the indigenous peoples and the outsiders. Some of these conflicts have led to violent deaths on both sides, especially in Sarawak.

Repeatedly, these encroachments and appropriations often result in conflicts between the indigenous peoples and the outsiders. Some of these conflicts have led to violent deaths on both sides, especially in Sarawak.

The new threat: oil palm plantation businesses

Together with logging and large-scale development projects, the rapid expansion of the oil palm plantation business into Orang Asal lands makes this sector the most conflict-ridden one in rural

Malaysia. Recent experiences in Sabah, Sarawak and Semenanjung Malaysia clearly attest to this.

The source of the conflict stems from the non-recognition of the native customary rights or the inherent land rights of the indigenous peoples. State governments unfortunately tend to side with the oil palm plantation businesses in this regard. This is despite the fact that the courts of this land have ruled that the Orang Asal do have rights to their lands although such lands may not have been registered or titled. The court decisions in question include those of Adong bin Kuwau & Ors v Kerajaan Negeri Johor & Anor [1997], Nor anak Nyawai and Ors v Borneo Pulp Plantation Sdn. Bhd [2001], and Sagong Tasi and Ors v Kerajaan Negeri Selangor and Ors [2002].

The environmental and social argument against oil palm plantations

Oil palm plantations are mono-cultures. It is an illusion to try to equate oil palm plantations with

forests. Their ecologies are completely different.In reality, oil palm development contributes to deforestation both directly and indirectly. In fact, from 1995-2000, based on government statistics in Sieh & Ahmad (2001), 86 per cent of all deforestation in Malaysia was attributed to oil palm development.

Furthermore, conversion of forests into oil palm plantations leads to the complete loss of some species of mammals, reptiles and birds, while encouraging the proliferation of others to the extent that they become pests. Plantations also infringe on the habitat of many endangered species such as the orang-utan, elephant, tiger and proboscis monkey and cause them to be killed or relocated.

Herbicide and pesticide run-offs as well as effluents from oil palm mills pollute water courses that are important for humans, agriculture as well as to aquatic life.

Invariably, as a result of these effects of forest clearing and oil palm planting, it is usually the indigenous peoples who bear the consequences of such environmental degradation.

BIG versus small

New oil palm plantations invariably begin with deforestation. Furthermore the legality of the acquisition of plantation lands is frequently disputed by indigenous landowners and the courts. As such, such agricultural expansion cannot be deemed sustainable by any stretch of the imagination. It is therefore rather deceitful to talk about producing “sustainable” palm oil when the conditions that gave rise to the creation of the oil palm plantation were not sustainable in the first place.

Criteria 4.1 and 4.2 apparently recognises this contradiction and makes “recovering biodiversity” its goal rather than maintaining or sustaining biodiversity in the first place.

Criteria 4.1 and 4.2 apparently recognises this contradiction and makes “recovering biodiversity” its goal rather than maintaining or sustaining biodiversity in the first place.

Clearly also, when oil palm plantation expansion impinges of the traditional territories of indigenous peoples, ignoring their rights to the land, ruining their livelihoods, or giving them a less-than-equitable deal in the enterprise, the palm oil that results from that activity cannot be deemed as “sustainable”.

BIG Business

Oil palm plantation businesses are invariably BIG. They are premised on the pursuit of maximising profits. An oil palm plantation business is therefore characterised by a monoculture crop, which is planted on a large acreage (invariably obtained through deforestation or appropriation of indigenous lands), and, being a business, where the pursuit of profit is foremost in its objectives.

Smallholder farms, on the other hand, are more socially responsive and environmentally responsible. They benefit the smallholders directly and more justly. Palm oil from smallholdings therefore has the better likelihood of being “sustainable”. Only the mechanics of a sustainable palm oil certification scheme such as that of the RSPO makes it difficult for the oil from the smallholdings to be certified as “sustainable”.

Some comments on some relevant RSPO principles and criteria affecting indigenous peoples

Principle 7 in particular appears to afford protection to indigenous peoples and local communities in the production of sustainable palm oil.

However, Criterion 1.1 brings up the ‘legal’ argument, as in the condition that there is “compliance with all applicable local, national and ratified international laws and regulations”. The fear is that those wanting to, can hide behind national laws that do not respect or recognise the rights of indigenous peoples, even though the courts may be inclined to do so. Furthermore, Malaysia has not ratified any of the relevant international conventions (such as ILO 169 and the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination), which have implications

for enforcing indigenous peoples’ rights in Malaysia and also in the context of the RSPO Principles & Criteria. This non-action on the part of the Malaysian government therefore makes several of the principles and criteria unenforceable, except by way of consensual willingness on the part of the producer.

Criterion 7.5 states that a comprehensive, participatory social impact assessment (SIA) is to carried out for all new plantings and that the results are to be incorporated into all planning and operations. But a “participatory social impact assessment” is usually done before the project in order to evaluate its impact and to help decisionmakers decide whether the project should go ahead or not. An SIA is not to be done in order to merely mitigate the impact of an already approved project.

Criteria 7.6, 7.7. and 7.8 (on the responsible development of new plantations) are positive inclusions. However, they relate only to future or planned plantations. They provide no avenue for correcting past wrongs or for ensuring that these wrongs are not rewarded with a certificate promoting the violator as a “sustainable” producer.

Criterion 8.1 (commitment to transparency) actually provides no commitment to transparency and allows the non-transparent producer to hide behind this criterion for the flimsiest of excuses.

Other protections requiredThe RSPO Principles and Criteria for sustainable palm oil is an admirable document – on the surface. Unfortunately it allows for multiple interpretations of certain phrases and can allow an otherwise credible and positive criterion to be diluted or misapplied. There is therefore a need for an unambiguous statement of intent that clearly sets out the objective of the palm oil certification scheme. Among the elements of this preamble should be statements like:

• The object of this scheme is to ensure that the production of sustainable palm oil has not created social injustice, caused environmental degradation or initiated conflict.

• That is to say, the goal is to sustain the livelihoods and rights of peoples and to sustain the health of the environment rather than sustaining the production and profitability of palm oil.

• The scheme aspires to the higher standard of corporate responsibility, social responsiveness and environmental protection than that as may be prescribed by national laws or current practices.

References used:

• AIDEnvironment, 2004. Fact-sheet on palm oil production in Southeast Asia.

• Friends of the Earth – England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2004. Greasy Palms.

• Jomo K. S. , et al, 2004. Deforesting Malaysia. UNRISD/Zed Books. London.

• A. Sieh (MPOB) and T.M.A. Tengku Ahmad (MARDI), 2001. The case study on Malaysian palm oil. Paper presented at the Regional UNCTAD workshop, Bangkok 3-5 April.

No comments:

Post a Comment