Transformation of the Iban land use system in post independence Sarawak.

by Dimbab Ngidang[Commentary by Sarawak Headhunter in red].

Introduction

Iban land use, their customary land tenure, and inheritance patterns have all undergone many changes in post-independence Sarawak. The purpose of this paper is to examine (1) how customary rights to land were created based on Iban customary law or adat and the relationship between customary tenure and land use; (2) the historical justification of customary tenure; (3) legal constraints on land use under customary law; (4) how inter-ethnic relations have affected, and been affected by land use patterns in Sarawak; (5) the impact of government-sponsored development programs on land use; and (6) the long-term ramifications and/or implications of these changes on property rights regimes in terms of landownership, inheritance, and accessibility to land resources in Iban communities today. These changes have been brought about by the compounding effects of several different factors: (1) the state legal system; (2) land administration policies and practices; and (3) the interplay of market forces and government programs, such as subsidy and involuntary resettlement schemes in the 1960s, the introduction of in situ land development programs in the 1980s, and the implementation of joint venture oil palm plantation projects in the 1990s, all of which were designed, among other things, to address rural poverty.

Unfortunately, the addressing of rural poverty got (purposely) lost somewhere along the way, probably when Taib Mahmud, the ruling elites, their administrative allies and business cronies and families realized just how lucrative and immense such opportunities were for their own unjust enrichment. Along with the realization that the rural poor could easily be divided and ruled - even and especially when deprived of their land - and the urban well to do either misled or subverted into supporting the so-called "politics of development", this combined with the full force of the "law" turned the very own people's representatives against them in favour of the politics of feudalism and exploitation.

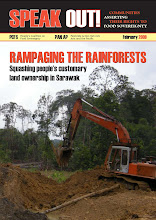

These different government-sponsored programs have helped to alter forest-fallow land use under shifting cultivation from a settled forest-fallow farming system to a mixed crop system. In addition, from 1995 onward, large areas of forest-fallow land held under native customary rights by members of the Iban community have been converted to oil palm plantations. The radical shift involved from subsistence to a commercial mode of production has changed the legal status of these ancestral lands. It has weakened the Iban land inheritance system based on adat by creating a new property rights regime. This regime in the case of joint venture oil palm projects creates the role of trustee as a custodian of native rights and dictates the transfer of land ownership from individual bilik (each "room" or unit of a longhouse) families to a joint venture company.

The question is can the trustee be trusted? This shift has not only merely weakened the Iban (and other native) land inheritance system based on adat but completely eliminated it without providing any alternative which may be likened to customary rights and practices and without any real benefits, whether short or long term.

Iban land use, their customary land tenure, and inheritance patterns have all undergone many changes in post-independence Sarawak. The purpose of this paper is to examine (1) how customary rights to land were created based on Iban customary law or adat and the relationship between customary tenure and land use; (2) the historical justification of customary tenure; (3) legal constraints on land use under customary law; (4) how inter-ethnic relations have affected, and been affected by land use patterns in Sarawak; (5) the impact of government-sponsored development programs on land use; and (6) the long-term ramifications and/or implications of these changes on property rights regimes in terms of landownership, inheritance, and accessibility to land resources in Iban communities today. These changes have been brought about by the compounding effects of several different factors: (1) the state legal system; (2) land administration policies and practices; and (3) the interplay of market forces and government programs, such as subsidy and involuntary resettlement schemes in the 1960s, the introduction of in situ land development programs in the 1980s, and the implementation of joint venture oil palm plantation projects in the 1990s, all of which were designed, among other things, to address rural poverty.

Unfortunately, the addressing of rural poverty got (purposely) lost somewhere along the way, probably when Taib Mahmud, the ruling elites, their administrative allies and business cronies and families realized just how lucrative and immense such opportunities were for their own unjust enrichment. Along with the realization that the rural poor could easily be divided and ruled - even and especially when deprived of their land - and the urban well to do either misled or subverted into supporting the so-called "politics of development", this combined with the full force of the "law" turned the very own people's representatives against them in favour of the politics of feudalism and exploitation.

These different government-sponsored programs have helped to alter forest-fallow land use under shifting cultivation from a settled forest-fallow farming system to a mixed crop system. In addition, from 1995 onward, large areas of forest-fallow land held under native customary rights by members of the Iban community have been converted to oil palm plantations. The radical shift involved from subsistence to a commercial mode of production has changed the legal status of these ancestral lands. It has weakened the Iban land inheritance system based on adat by creating a new property rights regime. This regime in the case of joint venture oil palm projects creates the role of trustee as a custodian of native rights and dictates the transfer of land ownership from individual bilik (each "room" or unit of a longhouse) families to a joint venture company.

The question is can the trustee be trusted? This shift has not only merely weakened the Iban (and other native) land inheritance system based on adat but completely eliminated it without providing any alternative which may be likened to customary rights and practices and without any real benefits, whether short or long term.

Background

The results of a planimetric survey carried out in 1976 (FAO 1980) revealed that out of a total of 12,325,208 hectares of land in Sarawak, 26% was cultivated in various crops. Twenty-three percent of this 26% was under shifting cultivation, 0.4% in wet rice, and 2.5% in various tree crops (rubber, pepper, cocoa, fruit trees, etc.). At any given time, large areas of land under shifting cultivation were left fallow and were held under native rights based on customary law or adat. The Iban farm over 69% of the total area cultivated, and accounted for 47% of all holdings. The Chinese farm 8% of the area and accounted for 16% of the holdings, and the Bidayuh farm 16% of the area and had a total of 11% of the holdings. The Malay and Melanau farm almost 6% and 4% of the area respectively, and accounted for 15% and 6% of the holdings.

The Iban community, which today constitutes 30.1% of the state population of 2.5 million people (Leete 2004), is the largest single ethnic group in Sarawak. Residing in more than 5,000 longhouses scattered throughout the rural areas of Sarawak, they are predominantly found in the Sri Aman, Betong, Kapit, Sibu, and Bintulu Divisions. Based on 69% of the total arable land area in Sarawak being cultivated by the Iban, the estimated cultivated area farmed by members of this group could be as high as 1,020,000 hectares out of the 1.5 million hectares of native customary land in Sarawak (Zainie 1997). This fact has significant implications for land administration policies and practices in Sarawak, especially with respect to poverty eradication and equity distribution in the context of Malaysia's "Vision 2020" policy.

Provided that there is a real system, of which there is none, in place and implemented for the purpose of the said poverty eradication and equity distribution, whether in the context of Malaysia's (in reality Mahathir's) "Vision 2020" policy or otherwise. Needless to say, this "Vision 2020" policy is just an excuse for further and greater exploitation of the rural poor especially, who have been systematically been deprived of not only their land but also their livelihood, pushing them deeper into poverty.

Land Use Under Customary Law

A close relationship between land, farming practices, and resource use among the Iban reveal important features of the community's agrarian roots. The traditional Iban farming system comprised a rich mixture of religious rites and cultural practices (Sather 1980, 1990 and Freeman 1955), and formed the basis upon which the pioneering ancestors of the present-day Iban first created customary rights to land in Sarawak.

Creation of customary rights to land and other natural resources within the territory of a longhouse community began when a ritual ceremony called panggul menoa was carried out by the pioneering ancestors in a particular area (Lembat 1994). Once this ritual has been performed, pioneering households known as bilik families would then clear plots of virgin jungle to establish individual parcels of farmland called tanah umai. These pioneering individuals who first cleared and cultivated the land thereby created rights to the land which were then passed on to their descendants through succeeding generations of bilik family members.

Individual plots of farmland are separated from one another by boundaries called antara umai in Iban. Traditionally, antara umai were demarcated by streams, rivers, watersheds, ridges, and other permanent landmarks used as natural boundaries between individual parcels of farmland. Such boundaries defined the size and extent of individual bilik rights over farmland. Rights of ownership are transferable in this system from parents to children. Distribution of plots of farmland among children is not necessarily equal. It is common among the Iban to accord more cultivation rights and privileges to children who look after ageing parents than to those who do not.

A territory or area of land which belongs to a longhouse community within defined boundaries is called its pemakai menoa in lban (Lembat 1994). Each pioneering longhouse has its own territorial domain. A longhouse is separated from others by a garis menoa (village boundary). The garis menoa is a very important mechanism for resource distribution among pioneering longhouse communities. It also functions as an important resource management strategy because it helps to define areas of constrained space and so reduces inter-community conflicts between pioneering longhouses. At the same time, it also regulates access to natural resources and cultivation rights among the members of the same longhouse within a pemakai menoa.

The pemakai menoa, both physically and as a concept, is central to Iban resource management. It is the hub of Iban resource tenure and, in a physical sense, constitutes a collective pool of natural resources, such as native farmland, fruit orchards or groves, primary and secondary forests and forest products (i.e., timber and wild vegetables, edible ferns and palm shoots, rattan, herbs and/or medicinal plants, fruit trees and bamboo); rivers and streams that run through a territory, and water catchments (Ngidang 2000, Lembat 1994, Richards 1961). Thus, pemakai menoa is the territorial domain of a longhouse community where customary rights to land and other natural resources were acquired by pioneering ancestors (Ngidang 2000).

Rights to a piece of land can be lost either by a transfer or when a person moves to another village through migration or pindah. Section 73 of Adat Iban (1) on pindah states that whoever moves from the longhouse to another "shall be deprived of all rights to untitled land or any customary land that has not been planted with crops and all such land shall be owned in common by the people of the longhouse." (2) (Majlis Adat Istiadat 1993: 31). If an individual or family migrates to another village from the longhouse (pindah), such rights can also be transferred to a relative who will in turn provide him with tungkus asi. The term tungkus asi describes a token gift provided by the recipient or as a form of compensation, "ganti tebi kapak, tebi beliong, a replacement of effort and the chipped axe blade, the rice eaten during clearing" (Richards 1961:42). Today, tungkus asi has been replaced a token monetary gift known as ganti rugi.

Thus tanah umai, or farmland, can be either private or common property, or both, depending on whether rights of access are held by individuals or by the community. A resource sharing concept is applied here when cultivation rights and rights of access to land are vested in the community. A community may invoke free access only to certain types of natural resources such as wild vegetables, shoots, etc. when taken for personal use. At the same time, it reserves the right to restrict access to resources which have a high economic value, such as rattan, timber, and fruit trees, the benefits of which are shared by the whole community.

It is customary to leave harvested farmlands fallow. Forest-fallowing as practiced by the Iban is divided into four main stages (Freeman 1955). The first stage of fallow is called jerami. The term jerami or redas (in the Batang Rajang area) refers to bush-fallow land at 1-2 years after a padi crop has been harvested. The next stage is temuda, which has a fallow period of 3-10 years, then damun with a fallow period ranging between 10-20 years. Finally, resembling virgin forest, pengerang is temuda which has been left uncultivated for more than 25 years.

Rights to cultivate temuda land initially belong to, and then are inherited from, the person who first felled the virgin forest. In the past, when resources were still abundant, any member of a longhouse had free access to resources in a temuda. For instance, he could take firewood and bamboo; gather wild fruits and vegetables, etc. without consulting the bilik family having cultivation rights over the land.

In addition, a longhouse community has its own forest reserve or pulau. The term pulau refers to an area of primary forest within a pemakai menoa. Pulau can be collectively owned under a common property regime and managed by a longhouse community, or individually owned. An individual creates the latter adjacent to the cultivated plot of land he first cleared at the time when a longhouse community established pemakai menoa. This reserve is called pulau umai and acts to preserve certain natural resources for future use. These resources can be rattan, tapang trees, fruit trees, timber, and so on. Rights of access to these resources belong to those who first cleared the land and to their descendants thereafter. In the case of community-owned pulau, there are four types of communal forest reserves set aside for hunting, gathering building materials and water catchments within a pemakai menoa.

During the process of creating a pemakai menoa in the pioneering days in the past, individuals might claim rights to a variety of special trees such as teras or belian, engkerebai (the fruits of which are used to produce textile dyes), engkabang, and tapang trees (the latter providing a place for honey bees to build hives). Tree tenure is established when the first person who finds the trees clears the undergrowth around them and thereby claims rights to these trees. Such rights were, and continue to be, heritable and passed down to the descendants of the claimant (cf. Sather 1990). The same applies to a planted tree; tenure rights apply to the tree and to the harvest of its fruits. Once an individual has tenure rights over certain trees, whether planted or found, the planter's or finder's descendants have the right to demand compensation if these trees are burned or felled by someone else.

Historical Justification of Customary Land Tenure

According to the Sarawak Land Code (SLC: Part II, page 27), (3) customary rights to land could only be created prior to 1 January 1958 in accordance with the native customary law of the community, based on any of the methods specified in Section 2, if a permit were obtained under section 10. In Section 5(2) of the Sarawak Land Code, these rights may be created by: (a) the felling of virgin jungle and the occupation of the land; (b) the planting of land with fruit trees; (c) the occupation or cultivation of land; (d) the use of land for a burial ground or shrine; (e) the use of land of any class for rights of way; or (f) any other lawful methods. However, historical evidence suggests that the above land law clearly reflected legislative efforts to deconstruct native rights and reconstruct them based on foreign laws, which were alien to the Iban community.

This law, enacted by the pre-independent Sarawak colonial powers, was never repealed after independence and joining of Sarawak in the formation of Malaysia. In fact it has served the ruling elite, especially under the regime of Taib Mahmud, to justify depriving the natives of their customary rights to land - where it cannot be proven by the natives that their customary tenure was established or created and dates prior to 1st January 1958. This has made many natives who purportedly practise customary rights over land mere trespassers and squatters and easy prey for an unscrupulous government and its equally unscrupulous business cronies and families.

It would be such an easy thing for the present government to recognize the practice of native customary rights by making a small amendment to the law to provide for the continuing creation of such rights up to the present day.

The fact that Taib Mahmud's present regime has not done so shows that it has no intention whatsoever of recognizing native customary rights created after 1st January 1958. This must be made clear to all natives so that they do not remain under any misconception that they can still create or practise their native customary rights to land after this date.

Sarawak, with two-thirds of its population indigenous Dayaks, (4) had a long history of Brunei rule prior to Brooke and colonial rule, and traditional land tenure, based on customary law or adat was in existence even before the Dayaks came under Brunei influence. Brooke land administration gave due recognition to the intimate relationship between adat and traditional land tenure.

The same cannot be said for the present Sarawak BN regime headed by Taib Mahmud, which has for its own devious purposes sought actively to disassociate such relationship between adat and customary land tenure, even to the extent of using police force to evict natives - without compensation - from the land upon which they and their families may have toiled and slogged for decades in favour of newcomer land developers.

Customary law or adat has always been instrumental in maintaining order and providing a state of balance between individuals, between individuals and the community, and between the community and the environment, both physical and spiritual (Langub 1999). Today, adat is still widely practiced among the Dayaks of Sarawak. It is under the custodianship of the village headman and a crucial aspect of adat (Richards 1961; Porter, 1967) is the definition of rules of access and rights of ownership to land and other natural resources within a longhouse territorial domain. Adat dictates the rules of inheritance and/or transferability of land from the pioneering ancestors to the present generation and is used by every longhouse community to regulate social relations and farming and other economic activities (Langub 1999). It is also a collective community framework for regulating resource utilization and management in a sustainable manner for the common good.

I am going on slowly and surely, basing everything on their own laws, consulting all their headmen at every step, reducing their laws to writing what I think right, merely in the course of conversation--separating the abuses from the customs... I follow,in preference, the plan of doing justice to the best of my ability in each particular case, adhering as nearly as possible, to the native law or customs.

(Quoted by Porter 1967:27.)

If even James Brooke could do this, why not the present BN state government under Taib?

Recognition of native customary law led James Brooke to provide an important provision in the Land Regulation of 1863, in which he declared that no scheme of alienation or land development should ever be introduced except in respect to land over which no rights had been established. The Code of Laws of 1842 permitted Chinese immigrants to settle only on lands not occupied by Malays or Dayaks. A paternalistic relationship between the White Rajah and the natives encouraged subservience to Brooke rule.

When James Brooke was installed the first Rajah of Sarawak in 1841, he deliberately created a dualistic political economy: commercial agriculture and mining for the Chinese immigrants, on the one hand, and a subsistence economy for the natives, on the other. Nevertheless, the Brookes did not encourage the development of large plantations in Sarawak. From 1841 to 1941, "Sarawak was run as a virtual personal kingdom by, in turn, James, Charles and Vyner Brooke," in which "government was an amalgam of autocracy and paternalism" (Cleary and Eaton 1996:7). Economic dualism reflected the Brookes' policy of non-interference in the native way of life. By invoking such policy, the Brooke administration also intentionally created legal pluralism (Hooker 1999) which defined and categorized two types of land tenure. One was based on native customary law or adat perpetuated among the natives. The other was a codified land system, which legalized private land ownership and supported the commercialization of agriculture.

Legal Constraints on Land Use Under Customary Tenure

1) The Iban Inheritance System

The most recent piece of legislation, which has far-reaching implications for the Iban land inheritance law, is the Land Code Amendment Bill 2000. As I have mentioned in the previous section, Section 5(2)(f) of the Sarawak Land Code states that land rights can also be created by "any other lawful methods" in addition to Section 5(2)(f) the felling of virgin jungle and the occupation of the land; (b) the planting of land with fruit trees; (c) the occupation or cultivation of land; (d) the use of land for a burial ground or shrine; (e) the use of land of any class for rights of way. Eaton (1997:7) views the provision in Section 5(2)(f) as a "catch-all clause that allowed for different rules or adat" (page 7). The Dayak community, especially the Iban, interprets this clause to mean that their cultural practices with respect to resource tenure and/or land use and their inheritance system, embodied in notions such as lanting or pesaka, are lawful. (5)

State authorities have interpreted Section 5(2)(f) of the State Land Code as redundant and ambiguous. Therefore, in their view, customary rights were not taken away when it was deleted. Zaine (1997) interpreted Section 5(2)(f) as a permit given in writing by a District Officer to fell virgin jungle in the interior land. To the indigenous peoples, Section 5(2)(f) is considered crucial to their customary rights because it integrated and codified their cultural practices in the Sarawak Land Code, therefore rendering these practices legal in their opinion. Customary law is a crucial component of their inheritance institutions and therefore a lawful part of their culture. By deleting Section 5(2)(f) from the Sarawak Land Code, it undermines the adat system because it potentially denies native peoples their right to continue the practice of their culture. They can no longer claim rights over their territorial domain (pemakai menoa) and communal forest (pulau galau) (Bian 2000). When culture is detached from rights to land, then the only means of claiming such rights to ancestral lands is through physical occupation. This can be problematic in the case of temuda land under forest-fallow cultivation.

Hollis (2000) argues that Section 5(2) places restrictions on native customary rights because there is no provision for determining the boundaries of ancestral lands. In the absence of written records, even if customary rights were acquired prior to 1 January 1958, lawful occupation is difficult to prove over time, especially when members of the older generations are dead. Again, as stated in the Sarawak Land Code, lawful occupation is allowed if the District Office grants written permission. The proof of lawful occupation is accepted if the evidence can be proved or verified by: (1) aerial photographs, (2) permit or certificate issued pursuant to Order No. VIII, 1920, (3) records kept by Native Courts pertaining to disputes over land claims, (4) proclamation or modification made under the Forests Ordinance, (5) physical occupation of the land coupled with evidence that such occupation began prior to 1 January 1958, or if after 1958, with a permit granted according to the provisions given under section 10 of the Sarawak Land Code.

2) The Forest-Fallow Farming System

Pioneer shifting cultivation on virgin forest land has not been practiced for a long time due, particularly during the last half century, to restrictions of the Land Code of 1958, the Forest Ordinance of 1953, the Wildlife Protection Ordinance of 1990, and the National Park and Natural Reserve bill (1998). Indeed, in some areas of Sarawak, pioneer cultivation appears to have ended much earlier. (6) What is considered shifting cultivation today is essentially the clearing of secondary forest or temuda for re-farming. This cyclic forest-fallow farming system is a common conservation practice among the indigenous peoples of Sarawak (Cramb and Willis 1990). As far as native customary land tenure is concerned, land under forest-fallow is never unoccupied, and more often than not, such land is planted with fruit trees and other tree crops, which is a common traditional agro-forestry practice, and hence the land is not "abandoned." Also, studies have shown that if the fallow period is long enough, shifting cultivation does not cause soil and forest degradation (Hatch 1982) and therefore, from a conservationist viewpoint, is not destructive to the environment.

Forest-fallow land has been subjected to various legislative constraints over the years and has been construed as abandoned or undeveloped in the Land Code and therefore as belonging to the State. Judging from the official argument, the only main reason why the forest-fallow farming system has been heavily criticized and perceived as wasteful by both the public and private sectors is due to an increasing demand for land for commercial plantations. Good agricultural land, which is suitable for commercial plantations, is found in areas where the Iban are practising a forest-fallow farming system. All these lands are classified as native customary land (NCL) in the Sarawak Land Code. These ancestral lands, which were once considered culturally related property by the Iban, have now become a sought-after commodity and the object of intense competition between various stakeholders.

3) Restoring Native Customary Rights

The issue of sovereignty and proprietary rights over land is a key point of contention between the government and the natives. Adat defines native customary rights to land as rights of ownership, whereas the Sarawak Land Code, which is an extension of Brooke and Colonial land laws, defines such rights as usufruct rights, which means only rights to use, but not to own, land (Porter 1967). Thus, in the context of the Land Code, natives do not have absolute rights to land; rather they merely have a bundle of rights. Therefore, ownership of land in Sarawak is regarded as ownership of parts of this bundle. "The bundle of rights is made up of rights belonging to the ruler, the tribe, the family, the village, the household and the individual" (Richards 1961:19). "A chief may have a right of control or even allocation but this too is limited by the rights of other members of the community to which he belongs" (1961:20). Richards points out that adat means law and is binding upon people without sovereign enforcement (1961:16). Because of contradicting interpretations of customary law related to land, efforts to integrate land rights into the Land Code have been problematic.

However, as clearly stated by Porter (1967:10), native customary tenure based on adat existed long before Brooke rule, and Dayak occupation and cultivation of land in Borneo for centuries was more than enough to justify their ownership of it. High Court Judge Ian Chin's 2002 judgment made a landmark decision in favor of the rights of the Iban in Sebauh, Bintulu Division, against the Borneo Pulp Plantation. The judge, in this historic judgment, supported this argument that natives do not owe their customary rights to statute. This judgment restores native rights to their ancestral lands, which have been unlawfully taken away from them since the Brooke era. This, according to Hooker (2002: 101), proves that "native rights have not been disturbed by past or contemporary legislation and so persist." The Sarawak government has appealed against the judgment, but the Court of Appeal has, at the time of writing, not yet fixed a hearing date.

Conflicting Economic Interests and Land Use

The Sarawak Land Code, which was legislated on 1 January 1958, was severely criticized in the 1959 Annual Report of the Land and Survey Department. It was stated that:

... the introduction of the Code was premature and its preparation should have been preceded by a review and clarification of Government policy regarding land and an attempt made to obtain some unification of more important principles of Native Customary Rights. The Code is extremely detailed and rigid and the effect of its application is to dictate rather than interpret Government Policy (Land Committee Report 1962).

In 1962, the colonial government commissioned the Land Committee to review policy and problems related to land administration in Sarawak. Following the Land Committee report, a Land Bill was introduced in 1965, which was intended to alienate more land to satisfy Chinese demands for farmland in places where communications were reasonably good, within reach of towns or bazaars. However, the bill was not passed by the state legislature due to strong protests against the idea of converting native customary land to Mixed Zone Land. While the Land Committee appreciated the urgent need of the Chinese for more land, the committee believed that natives must be protected from the disposing of their land until such time as they can protect themselves (Land Committee Report 1962:15).

After this aborted attempt at land reform, a new type of land conflict emerged. This was precipitated by an expansion of both the logging and plantation industries in Sarawak, starting in the 1970s and continuing through the 1990s. With declining timber resources in the 1990s, private developers, local planters and state agencies have turned their attention to areas of native customary land (NCL) as offering the greatest opportunities for commercial agriculture. An expansion of the plantation sector in Sarawak has given rise to conflicts both between natives and private developers, and between natives and political elites. These conflicts relate to differences in values regarding land use and to a lack of understanding on the part of private developers and elites of the psychological, social and cultural orientation of the local people affected by plantation expansion. On the surface, it looks as though natives view land solely as a means of livelihood, in contrast to the elites' view of land as a commodity to be traded on demand (Ngidang 2000). Ngidang's (2002) study of the response of landowners to joint venture oil palm projects in Ulu Teru and Kanowit refutes this notion. Instead, the findings reveal that natives value their land for a variety of reasons, ranging from heritage to savings and wealth for future generations.

A second source of conflict arises from overlapping claims by both natives and private investors regarding lands approved for plantation development. Unfortunately, when some private investors are given a provisional lease (PL) to carry out development activities in a particular locality, they tend to ignore specific conditions given to PL holders that they have to sort out land matters (such as the extent of NCL and the boundaries between NCL and state land) within a given development area through consultation with the affected population. Having a provisional lease does not entitle them to start their operation; only when they have fulfilled the conditions stipulated in the PL will they be given the lease. A major problem arises when investors ignore this and start operations despite unresolved claims by affected landowners having customary rights to the land designated for plantation development.

This of course is purposely done, with the active connivance of a complicit state government. With the power of the state behind them, they think that they can mistreat and abuse the natives as they like. Without prior consultation with the affected native landowners, they send their bulldozers in under protection of gangsters and the police and refuse to pay compensation for any damage caused. And what does the "trustee" or "custodian" (LCDA) do about it? Nothing, since its Chairman just happens to be the Chief Minister, Taib Mahmud.

Impact of Development Programs on Land Use

Government intervention efforts over the past four decades have had a significant impact on land use policies and practices in Sarawak, and these have brought about major changes in the mode of production in the agricultural sector. As a result, the Iban have shifted from a subsistence mode to a mixed farming mode by planting various cash crops such as pepper, rubber, and cocoa on a smallholder's basis. More recently, some communities have begun to participate in commercial oil palm plantations, in addition to continuing rice cultivation. These changes have reduced Iban dependency on hill rice cultivation, which in turn has propelled them to shift land use patterns from mainly subsistence production to semi- and fully commercial market production, such as involvement in plantation agriculture implemented under in situ land development programs or via joint venture oil palm projects.

1) Land Use Under Smallholder Production

If we examine the Agriculture Statistics published by the Department of Agriculture (DOA) from the 1960s to the 1990s, the estimated area of land under shifting cultivation does not seem to have changed a great deal over the years. The data indicate that 77,631 hectares of hill rice were planted in 1990/1991. About the same area (76,177 hectares) was cultivated in hill rice in 1996/97, as compared to 56,754 hectares of wet rice planted during the same period. These latter figures suggest that almost as much land is in wet rice as in hill rice. This seems unlikely. According to DOA, assistance to padi planting increased markedly from 1981 to 2003, and the Iban community planted 87% of 46,503 hectares under this scheme. In the Eighth Malaysia Plan, a total of 1,050 hectares were approved and are now in various stages of implementation in Iban areas.

Here it can be argued that intervention efforts in rural development, as well as individual initiative, have significantly changed Iban cropping patterns. Indeed, as Cramb (1988) notes, the lban had already begun, as a result of individual initiative, to plant cash crops such as rubber on their temuda land during the Brooke and colonial eras, in addition to growing hill rice as a staple food crop. Smallholder agriculture became the norm in most areas by the 1960s, involving a mixed crop system that capitalizes on crop diversification, rather than mono-cropping, to maximize land use and utilization of surplus family labor.

Three main tree crops have had crucial socio-economic impacts on land use among the Ibans since the 1960s. The first crop is rubber (or getah pera in Iban), planted as early as the 1920s by the Iban community on a small scale. Records of the development of rubber under assistance from DOA can be traced back to as early as 1956. A total 124,329 hectares of rubber were planted between 1956 and 2003. Of these, 80% were cultivated in Iban areas. Also, between 1996 and 2003, 9,395 hectares of mini rubber estates were established, of which 96% (9,010 hectares) were cultivated by the Iban and the remaining 4% were planted by Lun Bawang in the Lawas District. The rubber-planting scheme introduced in the 1960s provided an opportunity to Iban shifting cultivators to plant this cash crop on an extensive scale in addition to hill rice. Largely as a consequence, the area planted in rubber increased from 25,000 to 36,000 hectares in the Second Division from 1960 to 1972 (Cramb 1988).

The second important cash crop cultivated by the Iban is pepper. Immigrant Chinese in the Kuching and Sibu Divisions have grown this crop since Brooke rule (1841-1941). The Iban, on their own initiative, also cultivated this crop as early as the 1940s, but it was only after the introduction of a pepper subsidy scheme in 1972 that pepper became an important alternative source of cash income for the Iban farmers. The number of Dayaks involved in pepper cultivation increased steadily between 1984 and 2003. According to Morrison (1997), 82% of all 45,000 pepper holdings in Sarawak were owned by Dayaks, but the recent data provided by DOA show the figure as high as 83.2% of the approximately 12,2286 hectares planted in the crop to be owned by Dayaks, of whom 75% were Iban.

A third important crop is cocoa. It was introduced in 1969 under the Agriculture Diversification program and continued until 1984. By 1985 it became one of the major crop schemes under a separate program, the Cocoa Subsidy Scheme. Although a relatively latecomer to Iban farming, it had a significant impact on land utilization, at least briefly. In the 1980s, out of the 11,162 hectares of land planted with cocoa in Sarawak, the Iban farmed about 33%. The total area under cocoa cultivation reached 80,467 hectares in 1991, but declined rapidly to 23,218 hectares in 1996 due to slumping cocoa prices. This was a huge decline in cocoa-cultivating area in only 5 years and it appeared that cocoa was a failure and had little long-term effect on the livelihoods of the Iban. DOA discontinued the scheme in 1995. Today, most lands previously planted in cocoa are used for pepper cultivation or have been returned to forest-fallow.

2) Land Use Under Resettlement Schemes

A type of government-engineered project that has in some areas transformed Iban land use are resettlement farm schemes. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, about 15,000 hectares of NCL were acquired by the state government for various resettlement schemes in Sarawak. Beginning in 1964, just one year after Sarawak gained its independence, the state government carried out its first social experiment by relocating more than 1,000 Iban in land resettlement schemes. Between 1964 and 1970, a total of nearly 5,544.9 hectares of native customary land (NCL), which was traditionally under forest-fallow shifting cultivation, was acquired from host populations and subsequently converted to rubber schemes at Triboh, Melugu, Skrang, Meradong, Sibintek, Lambir and Lubai Tengah. These resettlement schemes were implemented at the height of the communist insurgency in Sarawak and during the military confrontation between Malaysia and Indonesia in the 1960s. The costs of development of the farm scheme were treated as loans to the settlers to be repaid in installments in the form of monthly deductions from the proceeds of the sale of rubber sheets to the Sarawak Land Development Board (SLDB). Most land titles are still in the SLDB's possession due to settlers' failure to repay their outstanding loans. The resettlement projects were a failure and had to be abandoned by the government in 1982.

In 1972, the state government acquired native customary lands in Nanga Skuau in the Sibu Division in order to resettle 400 Iban households from Oya. The resettlement scheme, implemented by the Rejang Security Command (RASCOM), was designed primarily to relocate Ibans who were being harassed by communist terrorists in the Sibu Division. Due to competing interests, the ultimate goals and priorities of the scheme had to be balanced between improving the lot of rural Iban and security interests of the nation-state. Mono-cropping of pepper was implemented, but due to disease infestation and low prices in the 1970s, this resettlement scheme, too, failed to achieve its goals.

In addition, the Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (FELCRA) was mandated to create cocoa resettlement schemes in the Sibu Division. These schemes also failed due to low prices. The status of land tenure for settlers, and whether they will be given rights of ownership to the farmland to which they were moved, or whether they are only residential laborers, is still not clear.

In 1982, another resettlement exercise was carried out in Batang Ai as a result of the construction of a hydroelectric power dam across Wong Irup in the Lubok Antu District. The objective of this relocation exercise was to supply hydro-electric power to meet the growing industrial needs of Sarawak and to provide the affected population with a better source of livelihood through the scheme (King 1986). The state and its political leaders argued that the affected communities must give way to development so that socioeconomic benefits could trickle down to them in return. About 10,300 hectares of native ancestral land were flooded, compelling the government to resettle more than 3,000 Ibans from 25 longhouse communities in Batang Ai to a new area--located just below the dam site. About 3,000 hectares of native ancestral land belonging to several longhouse communities at Nyemungan, Bintong, Bui, Sebangki and Ensawang were acquired to establish the farm scheme and for the construction of new longhouses.

Each longhouse community was allocated blocks of farmland classified as communal land, where each household was given 4.4 hectares of land. This farmland consisted of 2 hectares for rubber, 1.2 hectares for cocoa, and 0.4 hectare for a garden plot. Another 0.8 hectare of rice land was promised but has yet to be given. All plots of land which were previously planted with cocoa, have been replanted with oil palm in the last five years.

It is important to mention in passing that Iban settlers in the different resettlement schemes that we have mentioned were "landlords." They owned ancestral lands in their former longhouse areas, but without document of title. For objectives not of their own choice, they were relocated to other localities on land which belonged to other longhouse communities in order to satisfy military objectives or the economic interests of the state. In the process, native customary lands were acquired by the government and redistributed to settlers, which deprived the host population of its limited land resources.

Land ownership in all resettlement schemes is bestowed upon an individual settler, be it husband or wife. Farm schemes are registered under private ownership and become the private property of individual settlers. Because property rights are individualized, the system is contrary to the traditional Iban inheritance system. Second-generation settlers automatically become landless. Thus, by design, the system constitutes a push factor fostering out-migration from the scheme.

3) Land Use Under in situ Land Development Schemes

The first major effort to introduce commercial plantation agriculture to the Dayak community was carried out by the Sarawak Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (SALCRA) in 1976 after the failure of rubber-based resettlement schemes. Using an in situ land development program, large-scale oil palm plantations were implemented under the integrated agricultural development project concept. Today, 40,000 hectares have been developed using this in situ concept of land development that benefits about 12,000 households, of which slightly more than 50% are Iban and the rest Bidayuh. These projects are designed to consolidate idle Native Customary Land for plantation agriculture as a strategy for poverty eradication among the Dayaks under the New Economic Policy. Tracts of NCL are surrendered to the government for development, and SALCRA acts as a custodian of the land for a period of 25 years. The land is surveyed and documents of title in perpetuity are issued to the participating landowners.

Although SALCRA has been mandated to establish commercial plantations on idle NCL, it does not promote a mono-crop farming system. Rather, its ultimate goal is to diversify income-generating activities among the Iban, who have been over-dependent on subsistence farming for their livelihood. Thus, in contrast with the practice of resettlement schemes, where affected populations were, in virtually all cases (the Lambir LDS in the Miri Division was a partial exception), involuntarily relocated to a designated site for farm schemes, implementation of in situ land development projects takes into account the landowners' socio-cultural and psychological attributes. Landowners stay put in their longhouses and are encouraged to carry out stipulated agro-economic activities while participating in the farm schemes. This arrangement not only gives time for the Iban to adjust to the new farming system, but also encourages landowners to diversify their crops. Thus, a spillover effect of this scheme seems to intensify the utilization of NCL for the cultivation of various crops. The trustee's role, land codification process and farm scheme administration all favour the landowners in an affirmative action program implemented under the New Economic Policy.

Customary Land Banks Under the Joint-Venture Concept JVC

In 1995, the state government instituted a new land reform program under the joint-venture concept (JVC) of land development (Ngidang 1997, 2002). Under the JVC, a community which owns land teams up in partnership with the private sector that possesses capital and expertise to develop ancestral land into commercial plantations. About 300,000 hectares of NCL have been earmarked and/or approved by the Sarawak Ministry of Land and Rural Development for the purpose of establishing large-scale oil palm plantations in Sarawak.

1) Formation of Land Banks

One of the fundamental features of JVC partnership is the tripartite agreement. After a memorandum of consent has been signed by landowners, parcels of customary land within the territorial domain or pemakai menoa of a longhouse are declared as the development area. These lands are surveyed and consolidated into a land bank. The land bank is then surrendered to the managing agents, either to the Land Consolidation Development Authority (LCDA) and/or to the Sarawak Land Development Board (SLDB), which acts as the trustee for the NCL. The land bank is issued a master title and the land is then leased to a joint venture company. In this process, landowners and the managing agent have to sign two important agreements: a deed and a trust deed. The former specifies the duties, obligations, commitments, rights, benefits and responsibilities of parties involved. The latter deals with the protection of the land rights and/or interests of landowners.

2) Transfer of Ownership

The land bank is leased to the JVC for 60 years. However, this land bank cannot be mortgaged as collateral to secure any bank loan without the permission of the Sarawak Minister of Land and Rural Development. Throughout the duration of the lease, land ownership is legally transferred from the individual bilik families to a corporate body for a period of 60 years. This transfer of ownership requires a third agreement called the joint venture agreement to be executed between the managing agent (as a trustee) and a private investor.

Creation of the land bank under JVC, although it has potential socio-economic benefits, threatens the inheritance system of the Iban. When they surrender their lands to the JVC, land ownership has to be legally registered under private individuals, rather than the bilik family as a whole. This requires that parcels of NCL be divided among family members, which leads to land fragmentation. Thus, siblings of landowners and/or other family members, although they may still be living under the same roof, do not necessarily inherit the property from a parent, unless the parent makes a legal will to transfer such property to their children. This automatically renders much of the next generation landless.

3) Role of Trustee and Contract Arrangement

Under JVC, landowners collectively acquire a 30% stake in the joint venture company's share equity. The share equity of landowners under the joint venture arrangement is acquired through the lease value of NCL, which has been officially pegged at RM1200/hectare. Ten percent of the total equity in the company belongs to the trustee, while the remaining 60%, is owned by the investor.

This contract partnership involves trust between and/or among stakeholders: landowners, investors and trustees. This implies the three parties have entered into a covenant based on a contractual arrangement. Trust is "a state involving confident positive expectations about another's motives with respect to one's self in situations entailing risk," according to Boon and Holmes (1991:194). As stated earlier, the trust between landowners and government agents is sealed through two agreements: a deed and a trust deed. The contract is binding and therefore the rights and interests of landowners are taken over by the trustee, who acts on the landowners' behalf in the joint partnership throughout the duration of a 60-year lease.

The joint venture agreement between the managing agents (SLDB and LCDA) and the private investors provides the legal framework for the joint venture partnership. The JV agreement defines how partner co-operation operates and the contents of the deed and trust deed. Landowners are not represented on the board of directors of the JVC, despite having a 30% stake in the company. Despite being landlords, they have now been reduced to minority shareholders in a joint venture project.

However, one important safety net in this JV arrangement is that government policy does not allow the land bank to be used as collateral or shares of land to be disposed of without the permission of the Sarawak Minister of Rural and Land Development. In the event of bankruptcy, however, the majority shareholder can use the land bank as collateral or mortgage it for purposes totally at odds with the contractual agreements. This potential abuse of the collateral power of the land bank, of course, could happen under political pressure from a private investor, who holds a 60% stake in the joint venture project, especially in the absence of institutional constraints.

The Sarawak Land Code (SLC) does not guarantee automatic reversion of these lands upon expiry of the 60-year lease. In fact, Section 18A (3) of the Sarawak Land Code (SLC) states that:Conclusion

This paper has looked at the historical, sociological and cultural justifications of Iban customary land tenure, and its legal constraints under the Sarawak Land Code. Several factors are identified as responsible for reducing forest-fallow land use: individual initiative, direct government intervention via various agricultural subsidy schemes, resettlement exercises, in situ land development programs, land bank schemes under JVC and legislative changes in the Sarawak Land Code. Clearly, the dynamics of land use among the Iban have been closely associated with the coming together of political and economic interests of two dominant stakeholders: the private sector and public agencies.

Land utilization in the Iban community today is primarily characterized by mixed cropping, where forest-fallow still dominates. Commercial plantations made significant inroads into Iban community land during the 1980s and 1990s, but the area under plantations is still very small compared to land cultivated under rice and tree crops. Only a relatively small proportion of Iban lands are cultivated under terms of the SALCRA's in situ land development programs or JVC oil palm plantations, as compared to areas under diversified mixed farming.

It is argued that regardless of whether NCL is developed under resettlement schemes, through in situ land development programs, or under a JVC arrangement, all three strategies have long-term implications for native customary land tenure and affect the socio-economic well-being of the communities directly involved. Invariably, property rights change from collective heritable property to private, often non-heritable ownership in the case of land tenure under resettlement and in situ land development. A transfer of land ownership from individual families to a corporate body, in the case of land banks in JVC projects, also changes property rights, as does the trustee's role as custodian of native customary rights to land in JVC and SALCRA land development projects.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Clifford Sather, University of Helsinki, Jayl Langub, formerly of the Majlis Adat Istiadat, now the Institute of East Asian Studies, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, and Dr. Andrew Aeria, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

(1) Adat pindah was engineered by Rajah Charles Brooke as stated in the Fruit Tree Order in 1899 in order to stem the movement of Dayaks from one district to another (Porter 1967:13), because they were well known for their migratory pattern associated with "destructive" shifting cultivation (Freeman 1955).

(2) According to Pringle (1970), migration was associated with a quest for personal status and achievement and a desire for new areas to farm. For these reasons, the Iban were branded as aggressive migrants (Pringle 1970) and "destructive" shifting cultivators (Freeman 1955), whose movements had to be curtailed.

(3) Land classification in Sarawak divides land into five categories: 1) Mixed Zone Land, which refers to land that can be owned by both natives and non-natives; 2) Native Area Land held by natives under title; 3) Native Customary Land in which native customary rights, whether communal or otherwise, were lawfully created prior to 1st January 1958; 4) Reserve Land reserved for the government, including National Parks, Forest or Communal Forest; and 5) Interior Land which does not fall into any of the above categories.

(4) "Dayak" is a generic term that refers to tribal groups such as the Iban, Bidayuhs, Kayans, Kenyahs, Kelabits, Lum Bawangs, Penans, Berawans, Sihans, and others.

(5) Lanting is defined (in Adat Iban 1993, English Version, p. 14) as: "item or items of valuable property which may be chosen by the father and mother for their security before all the bilik property is divided to its members. It may be an old jar or gong or rubber garden or a piece of land, or any other valuable property of choice. It is inherited by whoever cares for him or her at the end of life." Pesaka is not explicitly defined in Adat Iban 1993, but is commonly understood to refer to any form of inherited property. Included in the notion is tanah pesaka, defined by Richards (1981:280), "land held under free title by persons native to Swk."

(6) Thus, according to Cramb (1988:106-107), for example, "by the middle of the 19th century the pioneer phase of Iban shifting cultivation in the Lupar and Saribas was largely completed." Similarly, Sather (1990) found, in collecting oral testimony relating to past land use, that pioneer cultivation had virtually ceased and been replaced by an established pattern of fallow-rotation throughout the Paku River region, a Saribas tributary, sometime shortly prior to James Brooke's arrival in Sarawak, by local reckoning, some 8 to 9 generations before the present.

References

Bian, B.

2000 Native Customary Land Rights in Sarawak: The Impact of Adong Case. A Paper Presented in a Conference on Customary Land Rights: Recent Development on 18-19 February 2000, organized by the Law Faculty of Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur.

Boon, S. D. and J. G. Holmes

1991 The Dynamics of Interpersonal Trust: Resolving Uncertainty in the Face of Risk. IN: R. A. Hinde and J. Grobel, eds., Cooperation and Prosocial Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University, pp. 190-211.

Cleary, M. and P. Eaton

1996 Tradition and Reform." Land Tenure and Rural Development in South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Cramb, R.A.

1988 The Commercialization of Iban Agriculture. IN: R. A. Cramb and R. H. W. Reece, eds., Development in Sarawak. Monash Paper on Southeast Asia, No. 17. Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, pp. 105-134.

Cramb, R. A. and I. R. Willis

1990 The Role of Traditional Institutions in Rural Development: Community-Based Land Tenure and Government Land Policy in Sarawak, Malaysia. World Development 18(3):347-360.

Eaton, P.

1997 Land Policy, Customary Rights and Rural Development. A Working Paper. Brunei: University of Brunei Darussalam.

FAO

1980 Policies, Programmes and Projects for Poverty Eradication in Sarawak. Report prepared for the Government of Malaysia. Rome: UNDP.

Freeman, J. D.

1955 Iban Agriculture. A Report on the Shifting Cultivation of Hill Rice by the Iban of Sarawak. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Hatch, T.

1982 Shifting Cultivation in Sarawak: A Review. Kuching: Soils Divisions, Research Branch, Department of Agriculture.

Hooker, M. B.

1999 A Note on Native Land Tenure in Sarawak. Borneo Research Bulletin 30:2840.

2002 Native Title in Malaysia Continued--Nor's Case. Australian Journal of Asian Law 4(1):92-105.

Hollis, C.

2000 Land Code (Amendment) Bill 2000. Available at http://www.rengah.c20.org/news

King, V. T.

1986 Planning for Agrarian Change: Hydro-electric Power, Resettlement and Iban Swidden Cultivators in Sarawak, East Malaysia. Occasional Paper No.11. Centre for South-East Asian Studies, University of Hull.

Langub, Jayl

1999 The Ritual Aspects of Customary Law in Sarawak with Particular Reference to the Iban. Journal of Malaysian and Comparative Law 25:45-60.

Leete, R.

2004 Paradox of Poverty Studies. A Paper Presented in a Seminar on Challenges and Responses to Poverty Eradication among Bumiputera Minorities in Sarawak organized by the Sarawak Dayak Graduates Association on 25 September 2004 at Crowne Plaza Riverside, Kuching.

Lembat, G.

1994 Native Customary Land and Adat. A Paper Presented in a Seminar on Pembangunan tanah pusaka bumiputera held in Santubong Hotel Resort on 29 September-3 October 1994.

Majlis Adat Istiadat

1993 Adat Iban 1993. Kuching: National Printing Press.

Morrison, P.

1997 Transforming the Periphery: The Case of Sarawak, Malaysia. IN: M. Watters and T. G. McGee, eds., Asia-Pacific New Geographies of the New Pacific Rim. London: Hurst & Company, pp. 302-317.

Ngidang, D.

1997 Native Customary Land Rights, Public Policy, Land Reform and Plantation Development in Sarawak. Borneo Review 8(1):63-80.

2000a A Clash Between Culture and Market Forces: Problems and Prospects for Native Customary Rights Land Development in Sarawak. IN: Michael Leigh, ed., Environment, Conservation and Land. Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial Borneo Research Council Conference, Borneo 2000. Kuching: Universiti Malaysia Sarawak and Sarawak Development Institute, pp. 237-250.

2000b Managing Natural Resources in the 1-ban Community. IN: Ministry of Social Development and Urbanization, Sarawak. Ethical Values of Sarawak's Ethnic Groups. Kuching: Dewan Bahasa & Pustaka, pp:32-42.

2002 Contradictions in Land Development Schemes: The Case of Joint Ventures in Sarawak. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 43(2):157-180.

Porter, A. F.

1967 Land Administration in Sarawak. Kuching: Government Printing Press.

Richards, A. J. N.

1961 Sarawak Land Law and Adat. Kuching: Government Printing Office.

Sarawak Government

1999 Laws of Sarawak: Land code chapter 81 (1958 edition). Kuching: State Attorney-General's Chambers.

1962 Land Committee Report. Kuching: Government Printing Press

Sather, Clifford

1980 Symbolic Elements in Saribas Iban Rites of Padi Storage. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of Royal Asiatic Society 53:67-95.

1990 Trees and Tree Tenure in Paku Iban Society: The Management of Secondary Forest Resources in a Long-Established Iban Community. Borneo Review 1(1):16-40.

Zaine, Z. K.

1997 Native Customary Rights and the Creation of Land Bank. Talimat Khas. Konsep Baru Pembangunan Tanah. Anjuran Bersama Kementerian Kemajuan Tanah and Angkatan Zaman Mansang Pada 30 Ogos 1997.

Dimbab Ngidang

Dayak Chair

Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS)

Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Malaysia

The results of a planimetric survey carried out in 1976 (FAO 1980) revealed that out of a total of 12,325,208 hectares of land in Sarawak, 26% was cultivated in various crops. Twenty-three percent of this 26% was under shifting cultivation, 0.4% in wet rice, and 2.5% in various tree crops (rubber, pepper, cocoa, fruit trees, etc.). At any given time, large areas of land under shifting cultivation were left fallow and were held under native rights based on customary law or adat. The Iban farm over 69% of the total area cultivated, and accounted for 47% of all holdings. The Chinese farm 8% of the area and accounted for 16% of the holdings, and the Bidayuh farm 16% of the area and had a total of 11% of the holdings. The Malay and Melanau farm almost 6% and 4% of the area respectively, and accounted for 15% and 6% of the holdings.

The Iban community, which today constitutes 30.1% of the state population of 2.5 million people (Leete 2004), is the largest single ethnic group in Sarawak. Residing in more than 5,000 longhouses scattered throughout the rural areas of Sarawak, they are predominantly found in the Sri Aman, Betong, Kapit, Sibu, and Bintulu Divisions. Based on 69% of the total arable land area in Sarawak being cultivated by the Iban, the estimated cultivated area farmed by members of this group could be as high as 1,020,000 hectares out of the 1.5 million hectares of native customary land in Sarawak (Zainie 1997). This fact has significant implications for land administration policies and practices in Sarawak, especially with respect to poverty eradication and equity distribution in the context of Malaysia's "Vision 2020" policy.

Provided that there is a real system, of which there is none, in place and implemented for the purpose of the said poverty eradication and equity distribution, whether in the context of Malaysia's (in reality Mahathir's) "Vision 2020" policy or otherwise. Needless to say, this "Vision 2020" policy is just an excuse for further and greater exploitation of the rural poor especially, who have been systematically been deprived of not only their land but also their livelihood, pushing them deeper into poverty.

Land Use Under Customary Law

A close relationship between land, farming practices, and resource use among the Iban reveal important features of the community's agrarian roots. The traditional Iban farming system comprised a rich mixture of religious rites and cultural practices (Sather 1980, 1990 and Freeman 1955), and formed the basis upon which the pioneering ancestors of the present-day Iban first created customary rights to land in Sarawak.

Creation of customary rights to land and other natural resources within the territory of a longhouse community began when a ritual ceremony called panggul menoa was carried out by the pioneering ancestors in a particular area (Lembat 1994). Once this ritual has been performed, pioneering households known as bilik families would then clear plots of virgin jungle to establish individual parcels of farmland called tanah umai. These pioneering individuals who first cleared and cultivated the land thereby created rights to the land which were then passed on to their descendants through succeeding generations of bilik family members.

Individual plots of farmland are separated from one another by boundaries called antara umai in Iban. Traditionally, antara umai were demarcated by streams, rivers, watersheds, ridges, and other permanent landmarks used as natural boundaries between individual parcels of farmland. Such boundaries defined the size and extent of individual bilik rights over farmland. Rights of ownership are transferable in this system from parents to children. Distribution of plots of farmland among children is not necessarily equal. It is common among the Iban to accord more cultivation rights and privileges to children who look after ageing parents than to those who do not.

A territory or area of land which belongs to a longhouse community within defined boundaries is called its pemakai menoa in lban (Lembat 1994). Each pioneering longhouse has its own territorial domain. A longhouse is separated from others by a garis menoa (village boundary). The garis menoa is a very important mechanism for resource distribution among pioneering longhouse communities. It also functions as an important resource management strategy because it helps to define areas of constrained space and so reduces inter-community conflicts between pioneering longhouses. At the same time, it also regulates access to natural resources and cultivation rights among the members of the same longhouse within a pemakai menoa.

The pemakai menoa, both physically and as a concept, is central to Iban resource management. It is the hub of Iban resource tenure and, in a physical sense, constitutes a collective pool of natural resources, such as native farmland, fruit orchards or groves, primary and secondary forests and forest products (i.e., timber and wild vegetables, edible ferns and palm shoots, rattan, herbs and/or medicinal plants, fruit trees and bamboo); rivers and streams that run through a territory, and water catchments (Ngidang 2000, Lembat 1994, Richards 1961). Thus, pemakai menoa is the territorial domain of a longhouse community where customary rights to land and other natural resources were acquired by pioneering ancestors (Ngidang 2000).

Rights to a piece of land can be lost either by a transfer or when a person moves to another village through migration or pindah. Section 73 of Adat Iban (1) on pindah states that whoever moves from the longhouse to another "shall be deprived of all rights to untitled land or any customary land that has not been planted with crops and all such land shall be owned in common by the people of the longhouse." (2) (Majlis Adat Istiadat 1993: 31). If an individual or family migrates to another village from the longhouse (pindah), such rights can also be transferred to a relative who will in turn provide him with tungkus asi. The term tungkus asi describes a token gift provided by the recipient or as a form of compensation, "ganti tebi kapak, tebi beliong, a replacement of effort and the chipped axe blade, the rice eaten during clearing" (Richards 1961:42). Today, tungkus asi has been replaced a token monetary gift known as ganti rugi.

Thus tanah umai, or farmland, can be either private or common property, or both, depending on whether rights of access are held by individuals or by the community. A resource sharing concept is applied here when cultivation rights and rights of access to land are vested in the community. A community may invoke free access only to certain types of natural resources such as wild vegetables, shoots, etc. when taken for personal use. At the same time, it reserves the right to restrict access to resources which have a high economic value, such as rattan, timber, and fruit trees, the benefits of which are shared by the whole community.

It is customary to leave harvested farmlands fallow. Forest-fallowing as practiced by the Iban is divided into four main stages (Freeman 1955). The first stage of fallow is called jerami. The term jerami or redas (in the Batang Rajang area) refers to bush-fallow land at 1-2 years after a padi crop has been harvested. The next stage is temuda, which has a fallow period of 3-10 years, then damun with a fallow period ranging between 10-20 years. Finally, resembling virgin forest, pengerang is temuda which has been left uncultivated for more than 25 years.

Rights to cultivate temuda land initially belong to, and then are inherited from, the person who first felled the virgin forest. In the past, when resources were still abundant, any member of a longhouse had free access to resources in a temuda. For instance, he could take firewood and bamboo; gather wild fruits and vegetables, etc. without consulting the bilik family having cultivation rights over the land.

In addition, a longhouse community has its own forest reserve or pulau. The term pulau refers to an area of primary forest within a pemakai menoa. Pulau can be collectively owned under a common property regime and managed by a longhouse community, or individually owned. An individual creates the latter adjacent to the cultivated plot of land he first cleared at the time when a longhouse community established pemakai menoa. This reserve is called pulau umai and acts to preserve certain natural resources for future use. These resources can be rattan, tapang trees, fruit trees, timber, and so on. Rights of access to these resources belong to those who first cleared the land and to their descendants thereafter. In the case of community-owned pulau, there are four types of communal forest reserves set aside for hunting, gathering building materials and water catchments within a pemakai menoa.

During the process of creating a pemakai menoa in the pioneering days in the past, individuals might claim rights to a variety of special trees such as teras or belian, engkerebai (the fruits of which are used to produce textile dyes), engkabang, and tapang trees (the latter providing a place for honey bees to build hives). Tree tenure is established when the first person who finds the trees clears the undergrowth around them and thereby claims rights to these trees. Such rights were, and continue to be, heritable and passed down to the descendants of the claimant (cf. Sather 1990). The same applies to a planted tree; tenure rights apply to the tree and to the harvest of its fruits. Once an individual has tenure rights over certain trees, whether planted or found, the planter's or finder's descendants have the right to demand compensation if these trees are burned or felled by someone else.

Historical Justification of Customary Land Tenure

According to the Sarawak Land Code (SLC: Part II, page 27), (3) customary rights to land could only be created prior to 1 January 1958 in accordance with the native customary law of the community, based on any of the methods specified in Section 2, if a permit were obtained under section 10. In Section 5(2) of the Sarawak Land Code, these rights may be created by: (a) the felling of virgin jungle and the occupation of the land; (b) the planting of land with fruit trees; (c) the occupation or cultivation of land; (d) the use of land for a burial ground or shrine; (e) the use of land of any class for rights of way; or (f) any other lawful methods. However, historical evidence suggests that the above land law clearly reflected legislative efforts to deconstruct native rights and reconstruct them based on foreign laws, which were alien to the Iban community.

This law, enacted by the pre-independent Sarawak colonial powers, was never repealed after independence and joining of Sarawak in the formation of Malaysia. In fact it has served the ruling elite, especially under the regime of Taib Mahmud, to justify depriving the natives of their customary rights to land - where it cannot be proven by the natives that their customary tenure was established or created and dates prior to 1st January 1958. This has made many natives who purportedly practise customary rights over land mere trespassers and squatters and easy prey for an unscrupulous government and its equally unscrupulous business cronies and families.

It would be such an easy thing for the present government to recognize the practice of native customary rights by making a small amendment to the law to provide for the continuing creation of such rights up to the present day.

The fact that Taib Mahmud's present regime has not done so shows that it has no intention whatsoever of recognizing native customary rights created after 1st January 1958. This must be made clear to all natives so that they do not remain under any misconception that they can still create or practise their native customary rights to land after this date.

Sarawak, with two-thirds of its population indigenous Dayaks, (4) had a long history of Brunei rule prior to Brooke and colonial rule, and traditional land tenure, based on customary law or adat was in existence even before the Dayaks came under Brunei influence. Brooke land administration gave due recognition to the intimate relationship between adat and traditional land tenure.

The same cannot be said for the present Sarawak BN regime headed by Taib Mahmud, which has for its own devious purposes sought actively to disassociate such relationship between adat and customary land tenure, even to the extent of using police force to evict natives - without compensation - from the land upon which they and their families may have toiled and slogged for decades in favour of newcomer land developers.

Customary law or adat has always been instrumental in maintaining order and providing a state of balance between individuals, between individuals and the community, and between the community and the environment, both physical and spiritual (Langub 1999). Today, adat is still widely practiced among the Dayaks of Sarawak. It is under the custodianship of the village headman and a crucial aspect of adat (Richards 1961; Porter, 1967) is the definition of rules of access and rights of ownership to land and other natural resources within a longhouse territorial domain. Adat dictates the rules of inheritance and/or transferability of land from the pioneering ancestors to the present generation and is used by every longhouse community to regulate social relations and farming and other economic activities (Langub 1999). It is also a collective community framework for regulating resource utilization and management in a sustainable manner for the common good.

In 1842 James Brooke cautiously introduced the Code of Laws, which was principally characterized by respect for people's customs and traditions. James said that:

I am going on slowly and surely, basing everything on their own laws, consulting all their headmen at every step, reducing their laws to writing what I think right, merely in the course of conversation--separating the abuses from the customs... I follow,in preference, the plan of doing justice to the best of my ability in each particular case, adhering as nearly as possible, to the native law or customs.

(Quoted by Porter 1967:27.)

If even James Brooke could do this, why not the present BN state government under Taib?

Recognition of native customary law led James Brooke to provide an important provision in the Land Regulation of 1863, in which he declared that no scheme of alienation or land development should ever be introduced except in respect to land over which no rights had been established. The Code of Laws of 1842 permitted Chinese immigrants to settle only on lands not occupied by Malays or Dayaks. A paternalistic relationship between the White Rajah and the natives encouraged subservience to Brooke rule.

When James Brooke was installed the first Rajah of Sarawak in 1841, he deliberately created a dualistic political economy: commercial agriculture and mining for the Chinese immigrants, on the one hand, and a subsistence economy for the natives, on the other. Nevertheless, the Brookes did not encourage the development of large plantations in Sarawak. From 1841 to 1941, "Sarawak was run as a virtual personal kingdom by, in turn, James, Charles and Vyner Brooke," in which "government was an amalgam of autocracy and paternalism" (Cleary and Eaton 1996:7). Economic dualism reflected the Brookes' policy of non-interference in the native way of life. By invoking such policy, the Brooke administration also intentionally created legal pluralism (Hooker 1999) which defined and categorized two types of land tenure. One was based on native customary law or adat perpetuated among the natives. The other was a codified land system, which legalized private land ownership and supported the commercialization of agriculture.

Legal Constraints on Land Use Under Customary Tenure

1) The Iban Inheritance System

The most recent piece of legislation, which has far-reaching implications for the Iban land inheritance law, is the Land Code Amendment Bill 2000. As I have mentioned in the previous section, Section 5(2)(f) of the Sarawak Land Code states that land rights can also be created by "any other lawful methods" in addition to Section 5(2)(f) the felling of virgin jungle and the occupation of the land; (b) the planting of land with fruit trees; (c) the occupation or cultivation of land; (d) the use of land for a burial ground or shrine; (e) the use of land of any class for rights of way. Eaton (1997:7) views the provision in Section 5(2)(f) as a "catch-all clause that allowed for different rules or adat" (page 7). The Dayak community, especially the Iban, interprets this clause to mean that their cultural practices with respect to resource tenure and/or land use and their inheritance system, embodied in notions such as lanting or pesaka, are lawful. (5)