Borneo hinge to Anwar's ambition

By Andrew Symon

Asia Times Online

SINGAPORE - If Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim is successful in his historic bid to form a reformist government in Kuala Lumpur, he will likely owe much to the country's Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak.

Anwar claimed on Tuesday he had secured the parliamentary numbers needed to topple Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi's beleaguered government and called for "handover talks" towards a peaceful political transition. The government refuted that claim, saying Anwar was employing the "politics of distraction" because he failed to achieve his avowed September 16 deadline to seize power through parliamentary defections.

The large, lightly populated and culturally distinctive northern coast of Borneo island, separated by the small oil rich Sultanate of Brunei, are now key to Anwar's ambitions. Should their members of parliament shift their loyalties away from the ruling Barison Nasional (BN) coalition government, their defections would be decisive for Anwar's Pakatan Rakyat alliance.

After the dramatic March 8 election, which saw the United Malays Nasional Organization (UMNO)-led BN coalition suffer its worse result since it first took government on independence from Britain in 1957, Sabah and Sarawak together now account for 55 out of the BN's 140 parliamentary seats. With Pakatan Rakyat holding sway over 82 seats, Anwar needs to woo a little over 50% of the Borneo seats to form a new government.

Helping Anwar's cause is the fact that about 40 of these 55 are from small parties in alliance with the dominant UMNO, which has led the national government and shaped Malaysia's political direction for five decades. To bring Borneo members on side, Anwar has offered to give the East Malaysian states a greater share of petroleum revenues, from 5% to 20% - an especially enticing offer given US$100 plus a barrel global oil prices - and greater autonomy generally.

Of the two states, it may be Sabah's MPs that are prone to lean first towards Anwar. With Sabah lagging well behind other Malaysian states in its level of economic development, Anwar has said greater petroleum revenue sharing would only be the redistributive start to remedy the BN's severe neglect of the state. According to the government's own national development plan, the incidence of poverty in Sabah is four times the national average.

Another point of contention between Sabah and the central government is the issue of illegal immigration, with many Sabahans feeling that Kuala Lumpur has not done enough to control the entry of migrants from nearby and even poorer southern Philippines and Indonesia. Anwar can also promise those BN MPs from Sabah who cross the floor some of the spoils of office, in terms of ministerial appointments in his new government.

The region's political dynamics and relationships with Kuala Lumpur are steeped in a complicated history. Formerly British crown colonies, and, before that, in the case of Sarawak, ruled by the so-called "White Rajah" Brookes family - three generations of Englishmen who fashioned the borders of present day Sarawak independent of London - and Sabah, once run by the British North Borneo Company, a company chartered by Queen Victoria, the two joined Malaya and Singapore to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963.

The lightly populated states, together making up just 5.5 million of Malaysia's 27 million, are socially and culturally different from peninsular Malaysia. Non-Muslim indigenous Dayak peoples of various tribes - Iban in Sarawak and Kadazan and Dusun in Sabah are the largest - are mostly Christian Anglicans or Catholics, along with ethnic Chinese, and make up the large majorities in both Sarawak and Borneo.

Muslim Malays and the small percentage of Dayaks who are Muslim make up less than 25% of the population in both states, compared to the peninsula where Muslim Malays make up about 60%. It is now notable that their federation with the peninsula in 1963 was a rush affair.

The British believed, in the Cold War context of the time, that both their and the region's best interests would be served by the incorporation of the two states into a new Malaysia, especially given the claims by Indonesia's president Sukarno that they should become part of Indonesian Kalimantan to the south. Intertwined with this was the fate of Singapore.

Arguments for the inclusion of Singapore into the new federation, argued by both the British and Singapore's leader, Lee Kuan Yew, could only be accepted by the UMNO, that is, Malay-led government in Kuala Lumpur of Tunku Abdul Rahman, if the Borneo states were also included.

Their Malay and Dayak populations would ensure a non-Chinese or bumiputra "sons of the soil" majority in the new Malaysia. (Singapore was later to go its own way after being pushed out of the federation by Kuala Lumpur in August 1965.) To make the federation attractive to Sarawak and Sabah, assurances were given by Tunku that their interests, as less economically developed and culturally distinctive states, would be protected. Various special autonomy powers were given to the two states.

Overlooked outback

The federation has proved, in fact, to be very successful. There has never been any talk of secession, despite periodic disagreements between state and national governments and the different characters of the Borneo states and the peninsula. But there still remains belief in Sarawak and Sabah that Kuala Lumpur takes more than it gives back and that their interests are often overlooked.

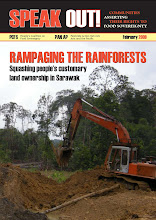

Within Sarawak and Sabah, although relations between the different racial and ethnic groups are generally good, there are still resentments among the indigenous non-Muslim Dayaks that they are not always getting a fair share and that their land rights are prone to abuse from large-scale timber, palm oil and other plantations and hydropower dam development, as the long-running controversies associated with the state-backed Bakun dam in Sarawak attest.

Non-Muslim Sabahans have also long been concerned at the apparent ease at which illegal Muslim immigrants were able to gain Malaysian citizenship papers in the 1980s and early 90s, thereby, some argue, adding support to the more Muslim focussed UMNO in Sabah. Certainly for the national government and development programs on the peninsula, the Borneo states have been a critical source of resource revenues, especially from oil and gas.

Sarawak has long been an important petroleum-producing province and now Sabah is joining it as a result of new and large deep water oil discoveries. Sarawak currently produces about 200,000 barrels of day of oil, or about 28% of national production. But it is natural gas that is most important in Sarawak with very large volumes - about three billion cubic feet per day, or 50% of national production - of offshore gas for the Bintulu liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal on the mid-coast run by Malaysia's state company, Petronas. At 23 million tons annual output capacity, it is one of the world's largest LNG facilities.

The Sarawak government, apart from its existing 5% upstream royalty on production also benefits from a minority stake in the downstream facility. An additional 15% royalty though would be a very substantial boost to state treasuries. But it is in Sabah where a 20% royalty would be a real and unprecedented bonanza and could go a long way to help Sabah overcome the development gap with the peninsula.

A huge increase in oil and gas production is forecast to come on line by the end of the next decade from deep water fields offshore. Until now, Sabah has produced only a modest volume of oil and gas, so petroleum has not featured greatly in the state and Kuala Lumpur's political equations. But all this is changing. New deep water exploration in depths of more than 200 meters, by the US's Murphy Oil and Shell has revealed major deposits.

By the middle to end of the next decade, this deep water frontier is anticipated by Petronas, to be adding of the order of 300,000 barrels per day and one billion cubic feet per day of gas to national output. The significance of these volumes is underlined by the fact that oil production at this scale would be about 45% of the country's present total output while the natural gas output would be about 16% of present production.

Plans for the commercialization of Sabah gas are ambitious. Petronas aims to take the offshore gas to shore and then pipe it 500 kilometers overland through Sabah and into neighboring Sarawak to the Bintulu LNG facility. The route which takes the $620 million pipeline behind the Brunei borders in Sarawak would pass through rugged mountainous terrain and over rivers before running along the more benign Sarawak coastal plain to Bintulu.

For Sabah members of parliament, with all these new revenues poised to come on-stream, Anwar's promise of a larger slice of the pie has them salivating. The problem for Anwar is that having shown his Borneo cards after the March election, the government has had time to try counter at least some of his moves by also promising a better deal - although not being specific about any changes to petroleum revenue sharing - and new development funding and programs for Sarawak and Sabah.

So, it may yet turn out that the safest strategy for the Borneo MPs is to work both ends to the middle, and enjoy a new importance in the BN coalition government without risking all by joining Anwar's Pakatan Rakyat. It's not clear yet if that political calculation has set back Anwar's bid to seize power on Tuesday. But what is clear is that how Sabah and Sarawak go, so too will Malaysia’s government.

Andrew Symon is a Singapore-based writer and analyst specializing in energy and resources and a frequent visitor to Sarawak and Sabah. He may be reached at andrew.symon@yahoo.com.sg

By Andrew Symon

Asia Times Online

SINGAPORE - If Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim is successful in his historic bid to form a reformist government in Kuala Lumpur, he will likely owe much to the country's Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak.

Anwar claimed on Tuesday he had secured the parliamentary numbers needed to topple Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi's beleaguered government and called for "handover talks" towards a peaceful political transition. The government refuted that claim, saying Anwar was employing the "politics of distraction" because he failed to achieve his avowed September 16 deadline to seize power through parliamentary defections.

The large, lightly populated and culturally distinctive northern coast of Borneo island, separated by the small oil rich Sultanate of Brunei, are now key to Anwar's ambitions. Should their members of parliament shift their loyalties away from the ruling Barison Nasional (BN) coalition government, their defections would be decisive for Anwar's Pakatan Rakyat alliance.

After the dramatic March 8 election, which saw the United Malays Nasional Organization (UMNO)-led BN coalition suffer its worse result since it first took government on independence from Britain in 1957, Sabah and Sarawak together now account for 55 out of the BN's 140 parliamentary seats. With Pakatan Rakyat holding sway over 82 seats, Anwar needs to woo a little over 50% of the Borneo seats to form a new government.

Helping Anwar's cause is the fact that about 40 of these 55 are from small parties in alliance with the dominant UMNO, which has led the national government and shaped Malaysia's political direction for five decades. To bring Borneo members on side, Anwar has offered to give the East Malaysian states a greater share of petroleum revenues, from 5% to 20% - an especially enticing offer given US$100 plus a barrel global oil prices - and greater autonomy generally.

Of the two states, it may be Sabah's MPs that are prone to lean first towards Anwar. With Sabah lagging well behind other Malaysian states in its level of economic development, Anwar has said greater petroleum revenue sharing would only be the redistributive start to remedy the BN's severe neglect of the state. According to the government's own national development plan, the incidence of poverty in Sabah is four times the national average.

Another point of contention between Sabah and the central government is the issue of illegal immigration, with many Sabahans feeling that Kuala Lumpur has not done enough to control the entry of migrants from nearby and even poorer southern Philippines and Indonesia. Anwar can also promise those BN MPs from Sabah who cross the floor some of the spoils of office, in terms of ministerial appointments in his new government.

The region's political dynamics and relationships with Kuala Lumpur are steeped in a complicated history. Formerly British crown colonies, and, before that, in the case of Sarawak, ruled by the so-called "White Rajah" Brookes family - three generations of Englishmen who fashioned the borders of present day Sarawak independent of London - and Sabah, once run by the British North Borneo Company, a company chartered by Queen Victoria, the two joined Malaya and Singapore to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963.

The lightly populated states, together making up just 5.5 million of Malaysia's 27 million, are socially and culturally different from peninsular Malaysia. Non-Muslim indigenous Dayak peoples of various tribes - Iban in Sarawak and Kadazan and Dusun in Sabah are the largest - are mostly Christian Anglicans or Catholics, along with ethnic Chinese, and make up the large majorities in both Sarawak and Borneo.

Muslim Malays and the small percentage of Dayaks who are Muslim make up less than 25% of the population in both states, compared to the peninsula where Muslim Malays make up about 60%. It is now notable that their federation with the peninsula in 1963 was a rush affair.

The British believed, in the Cold War context of the time, that both their and the region's best interests would be served by the incorporation of the two states into a new Malaysia, especially given the claims by Indonesia's president Sukarno that they should become part of Indonesian Kalimantan to the south. Intertwined with this was the fate of Singapore.

Arguments for the inclusion of Singapore into the new federation, argued by both the British and Singapore's leader, Lee Kuan Yew, could only be accepted by the UMNO, that is, Malay-led government in Kuala Lumpur of Tunku Abdul Rahman, if the Borneo states were also included.

Their Malay and Dayak populations would ensure a non-Chinese or bumiputra "sons of the soil" majority in the new Malaysia. (Singapore was later to go its own way after being pushed out of the federation by Kuala Lumpur in August 1965.) To make the federation attractive to Sarawak and Sabah, assurances were given by Tunku that their interests, as less economically developed and culturally distinctive states, would be protected. Various special autonomy powers were given to the two states.

Overlooked outback

The federation has proved, in fact, to be very successful. There has never been any talk of secession, despite periodic disagreements between state and national governments and the different characters of the Borneo states and the peninsula. But there still remains belief in Sarawak and Sabah that Kuala Lumpur takes more than it gives back and that their interests are often overlooked.

Within Sarawak and Sabah, although relations between the different racial and ethnic groups are generally good, there are still resentments among the indigenous non-Muslim Dayaks that they are not always getting a fair share and that their land rights are prone to abuse from large-scale timber, palm oil and other plantations and hydropower dam development, as the long-running controversies associated with the state-backed Bakun dam in Sarawak attest.

Non-Muslim Sabahans have also long been concerned at the apparent ease at which illegal Muslim immigrants were able to gain Malaysian citizenship papers in the 1980s and early 90s, thereby, some argue, adding support to the more Muslim focussed UMNO in Sabah. Certainly for the national government and development programs on the peninsula, the Borneo states have been a critical source of resource revenues, especially from oil and gas.

Sarawak has long been an important petroleum-producing province and now Sabah is joining it as a result of new and large deep water oil discoveries. Sarawak currently produces about 200,000 barrels of day of oil, or about 28% of national production. But it is natural gas that is most important in Sarawak with very large volumes - about three billion cubic feet per day, or 50% of national production - of offshore gas for the Bintulu liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal on the mid-coast run by Malaysia's state company, Petronas. At 23 million tons annual output capacity, it is one of the world's largest LNG facilities.

The Sarawak government, apart from its existing 5% upstream royalty on production also benefits from a minority stake in the downstream facility. An additional 15% royalty though would be a very substantial boost to state treasuries. But it is in Sabah where a 20% royalty would be a real and unprecedented bonanza and could go a long way to help Sabah overcome the development gap with the peninsula.

A huge increase in oil and gas production is forecast to come on line by the end of the next decade from deep water fields offshore. Until now, Sabah has produced only a modest volume of oil and gas, so petroleum has not featured greatly in the state and Kuala Lumpur's political equations. But all this is changing. New deep water exploration in depths of more than 200 meters, by the US's Murphy Oil and Shell has revealed major deposits.

By the middle to end of the next decade, this deep water frontier is anticipated by Petronas, to be adding of the order of 300,000 barrels per day and one billion cubic feet per day of gas to national output. The significance of these volumes is underlined by the fact that oil production at this scale would be about 45% of the country's present total output while the natural gas output would be about 16% of present production.

Plans for the commercialization of Sabah gas are ambitious. Petronas aims to take the offshore gas to shore and then pipe it 500 kilometers overland through Sabah and into neighboring Sarawak to the Bintulu LNG facility. The route which takes the $620 million pipeline behind the Brunei borders in Sarawak would pass through rugged mountainous terrain and over rivers before running along the more benign Sarawak coastal plain to Bintulu.

For Sabah members of parliament, with all these new revenues poised to come on-stream, Anwar's promise of a larger slice of the pie has them salivating. The problem for Anwar is that having shown his Borneo cards after the March election, the government has had time to try counter at least some of his moves by also promising a better deal - although not being specific about any changes to petroleum revenue sharing - and new development funding and programs for Sarawak and Sabah.

So, it may yet turn out that the safest strategy for the Borneo MPs is to work both ends to the middle, and enjoy a new importance in the BN coalition government without risking all by joining Anwar's Pakatan Rakyat. It's not clear yet if that political calculation has set back Anwar's bid to seize power on Tuesday. But what is clear is that how Sabah and Sarawak go, so too will Malaysia’s government.

Andrew Symon is a Singapore-based writer and analyst specializing in energy and resources and a frequent visitor to Sarawak and Sabah. He may be reached at andrew.symon@yahoo.com.sg

3 comments:

Sarawak and Sabah must wake up and stake their claim as active partners within the Malaysian governance. Sbah and Sarawak also needs to have its autonomous aspect preserved

Well, well, well! To think that today Sabah and Sarawak are the kingmakers. Who would have thought it 45 years ago? Not long after the formation of Malaysia I remember being told by a relative, who had dealings with the Federal govt., being told by a Federal minister that Sarawak was a country cousin!

Sarawak and Sabah have woken up. What can stupid anwar do if he becomes PM? Brag, brag only kah.

Stupid Sarawkian support him.

Post a Comment