PRESS RELEASE JUNE 21, 2007

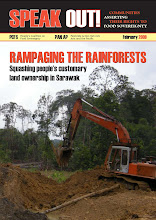

PRESS RELEASE JUNE 21, 2007Approval of Plantation Projects in the Bakun Catchment Area between 1999 and 2002: SAM Calls for Transparency and Accountability in Sarawak

SAM is shocked to learn recently that between 1999 and 2002, three huge plantation projects, which are largely located within the Bakun catchment, have been approved by the Sarawak state government. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports for the projects were approved between 2000 and 2003.

In an effort to counter mounting criticisms against the Bakun Hydroelectric Project, from 1995 to 2001, several of our Federal ministers have promised that the 1.5 million ha Bakun Catchment Area, a mostly forested region, will soon be gazetted in order to protect the dam. As a matter of fact, our then Deputy Prime Minister himself was widely quoted by local newspapers on March 13, 1996 stating that “we should realise that we will gazette a catchment area covering 1.5 million hectares which may not have been created if the Bakun project is not implemented.”

However today, three projects have been approved in the catchment – the Shin Yang Forest Plantation located in the Murum river basin (155,930 ha), the Bahau-Linau Forest Plantation (108,235 ha) and the Merirai-Balui Forest Plantation (55,860 ha). Both Bahau-Linau and Merirai-Balui, owned by a subsidiary of Rimbunan Hijau, will be establishing pulp and wood tree monocultures while Shin Yang, owned by Shin Yang Forestry, is also undertaking oil palm cultivation. Actual cultivation areas of such plantations will typically cover between 50 and 60 percent of the total concession areas.

The Bakun reservoir catchment comprises some 20 sub-catchments. The main river draining the catchment is the Balui, which in turn is fed by the Murum, Bahau and Linau Rivers. According to the Bakun EIA reports themselves, the annual sediment load in the catchment had jumped from 11 to 29 million tonnes between 1983 and 1993 alone, which can largely be attributed to the advent of timber harvesting activities in the area.

Thus the establishment of plantations in the upstream reaches of Bakun will surely spell a disaster for the dam since such plantations will entail clear-cutting and periodic harvesting and an increase in erosion and siltation rates. Fast growing wood trees would involve cropping cycles of between 10 and 25 years while oil palm will reach its maximum productivity level after 25 years.

The approval of the plantation projects not only violates the promises made by government officials since 1995, but it also contradicts the many recommendations made by the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports for Bakun.

The Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for Bakun, attached as Appendix 6 to the EIA reports, notes that in areas where rapid forest regrowth is expected, future logging should be controlled to reduce siltation and the sediment load reaching the reservoir. The same also applies to the largest source of sediment associated with land clearing in the catchment above the reservoir inundation limit. In the long-term, prudent land use management for the catchment must be introduced, one which is based on the principle that the highest and best use of the catchment is the uninterrupted supply of quality water to the reservoir. This is also the fundamental position recommended in the Annex 4 of the EIA for Reservoir Preparation, which details the rationale and requirements for the catchment management of the dam.

Further, a Catchment Management Plan is supposed to have been developed by the project owner, a guide document to address the requirements for the optimum and sustainable utilisation of the catchment resources, emphasising the priority of securing the supply and storage of water.

Hence, how these projects for the plantations were approved in the first place remain a mystery.

All these bring us to the question of the transparency in land and forest governance matters in Sarawak. The Bakun EIA process itself was approved amidst much controversy in 1995 when it was discovered that the Federal Environmental Quality Act 1974 (EQA) was retrospectively amended to allow the authority of the EIA approval for certain projects in Sarawak to be transferred to the Natural Resources and Environment Board (NREB) which is subject to the Sarawak Natural Resources and Environment Ordinance 1994 (SNREO).

Unlike the EIA requirements in Peninsular Malaysia, the law in Sarawak excludes public participation in the EIA process, unless the project proponent so desires. As a result of this exclusion, today, the nature of the EIA process in Sarawak is non-transparent and contrary to good governance, as there is no right given to the public to give feedback prior to EIA approvals.

This is also the case in relation to the EIA approval for the three plantation projects above. Unsurprisingly, we had found several shortcomings in them.

Although all three reports mention their close proximity to the dam, they do not devote serious attention to the matter other than offering some mitigation measures. Reports for both of the Rimbunan Hijau projects while confident that their mitigation measures will be able to reduce sediment load to the dam, also casually notes that it would be almost impossible to accurately predict the magnitude of soil erosion that will occur when the plantation is harvested in 15 to 20 years. The reports also briefly mention that the question of allowing plantation developments in the catchment area is a policy matter that only the Sarawak Chief Minister who is also the Minister of Planning and Resource Management could decide. Thus, it is then assumed that if the projects have been approved, then all such concerns must have been adequately considered, in spite of the flawed EIA process mentioned above.

Meanwhile the Shin Yang project, which is located only 13 km above the dam, makes the gross error of boldly stating that there are no permanent settlements within their project area. SAM has managed to document the existence of at least five Penan settlements in the vicinity, which include Long Peran/Menapa, Long Singu, Long Luar, Long Tangau and Long Pelutan. The existence of several Penan communities in the area can easily be verified by official records of the Belaga District, the Bakun EIA reports, anthropological studies and even the famed Oxford University Expedition to Sarawak in 1955. Today, the affected peoples' livelihoods and access to clean water have been severely threatened with the degradation of their land.

We therefore demand an explanation from both the Federal and State authorities as to how these plantation projects were approved contrary to the previous promises made and the recommendations contained in the Bakun EIA reports.

Further, given the lack of transparency in the issuance of forestry licences and approval of plantation projects in sensitive ecosystems, as well as the lack of public consultation prior to all EIA approvals, we call upon the Sarawak state government to amend the existing law relating to the EIA process and allow for public participation and scrutiny prior to the approval of the EIA reports in the state, especially for logging and plantation projects. It is scandalous that the Sarawak EIA process does not follow that which exists in the Peninsula. It is time that this is rectified, in the light of the approvals given to the plantation projects in the Bakun Catchment Area.

S.M.Mohamed Idris

President

No comments:

Post a Comment