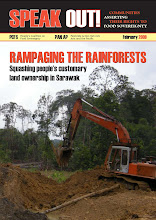

From The Malaysian Insider, Wed. 22nd July, 2009

JULY 22 — I must apologise for the delay in giving this critique. The Court of  Appeal gave its decision on July 2. I received the “Outline of Reasons” from Ngan Siong Hing only last Friday, July 17. Without him supplying me with a copy of the judgment of the Court of Appeal I would not be able to write this critique. Also as I do not have access to a law library I depend a lot on his generosity to get the legal material that I need to write my essays for ordinary people to understand what the judges are talking about. This is to enable the common people of this country to judge the judges for themselves.

Appeal gave its decision on July 2. I received the “Outline of Reasons” from Ngan Siong Hing only last Friday, July 17. Without him supplying me with a copy of the judgment of the Court of Appeal I would not be able to write this critique. Also as I do not have access to a law library I depend a lot on his generosity to get the legal material that I need to write my essays for ordinary people to understand what the judges are talking about. This is to enable the common people of this country to judge the judges for themselves.

Appeal gave its decision on July 2. I received the “Outline of Reasons” from Ngan Siong Hing only last Friday, July 17. Without him supplying me with a copy of the judgment of the Court of Appeal I would not be able to write this critique. Also as I do not have access to a law library I depend a lot on his generosity to get the legal material that I need to write my essays for ordinary people to understand what the judges are talking about. This is to enable the common people of this country to judge the judges for themselves.

Appeal gave its decision on July 2. I received the “Outline of Reasons” from Ngan Siong Hing only last Friday, July 17. Without him supplying me with a copy of the judgment of the Court of Appeal I would not be able to write this critique. Also as I do not have access to a law library I depend a lot on his generosity to get the legal material that I need to write my essays for ordinary people to understand what the judges are talking about. This is to enable the common people of this country to judge the judges for themselves.The whole case can be understood just by reading sections 418A(1) and (2), and 376(1) and (2) of the Criminal Procedure Code.

Power corrupts

David Pannick in his book Judges, OUP (1987), wrote at p. 76:

In all societies throughout history, judges have occasionally been adversely affected by their power. An early example occurs in the biblical story of Daniel and Susanna. Two elders of the community were appointed to serve as judges. They saw Susanna walking in her husband’s garden “and they were obsessed with lust for her”. When she resisted their advances they falsely accused her of infidelity to her husband. “As they were elders of the people and judges, the assembly believed them and condemned her to death”. A young man named Daniel protested that an enquiry should be made into the judges’ allegations. He accused them of giving “unjust decisions, condemning the innocent and acquitting the guilty”. Under his careful cross-examination, the judges were proved to be liars: Daniel and Susanna in The Apocrypha.

The English Bench has had its fair share of bad judges. … In the seventeenth century, the Bench “was cursed by a succession of ruffians in ermine [most notably Jeffreys and Scroggs (Sir William)], who, for the sake of court [royal] favour, violated the principles of law, the precepts of religion, and the dictates of humanity”: John Lord Campbell, Lives of the Lord Chancellors (5th edn, 1868), vol. 4, p. 416.

The misuse of power from whatever quarter it may come

In The Family Story, Butterworths (1981), Lord Denning said at p. 179:

The law itself should provide adequate and efficient remedies for the abuse or misuse of power from whatever quarter it may come. No matter who it is — who is guilty of the abuse or misuse. Be it government, national or local. Be it trade unions. Be it the press. Be it management. Be it labour. Whoever it be, no matter how powerful, the law should provide a remedy for the abuse or misuse of power. Else the oppressed will get to the point when they will stand it no longer. They will find their own remedy. There will be anarchy. To my mind it is fundamental in our society that a judge should do his utmost to see that powers are not abused or misused. If they come into conflict with the freedom of the individual — or with any other of our fundamental freedoms — then it is the province of the judge to hold the balance between the competing interests. In holding that balance the judges must put freedom first.

And at p. 180, this was what Lord Denning said in 1949 at the Hamlyn lectures:

Reviewing the position generally, the chief point which emerges is that we have not yet settled the principles upon which to control the new powers of the executive. No one will suppose that the executive will never be guilty of the sins that are common to all of us. You may be sure that they will sometimes do things which they ought not to do: and will not do things that they ought to do. But if and when wrongs are thereby suffered by any of us, what is the remedy? Our procedure for securing our personal freedom is efficient, but our procedure for preventing the abuse is not. Just as the pick and shovel is no longer suitable for the winning of coal, so also the procedure of mandamus, certiorari, and actions on the case are not suitable for the winning of freedom in the new age. They must be replaced by new and up-to-date machinery, by declarations, injunctions, and actions for negligence: and, in judicial matters, by compulsory powers to order a case stated. This is not a task for Parliament. Our representatives there cannot control the day-to-day activities of the many who administer the manifold activities of the State: nor can they award damages to those who are injured by any abuses. The courts must do this. Of all the great tasks that lie ahead, this is the greatest. Properly exercised the new powers of the executive lead to the welfare State: but abused they lead to the totalitarian State. None such must ever be allowed in this country. We have in our time to deal with changes which are of constitutional significance to those which took place 300 years ago. Let us prove ourselves equal to the challenge.

“That lecture was given in 1949. Now, 30 years or so later [The Family Story was published in 1981], I think we can say that we have achieved what I then hoped for,” wrote Lord Denning.

“We have now new and up-to-date machinery for the winning of freedom.” he wrote. “We have declarations, injunctions, actions for negligence, and judicial review. All that is needed now is for the judges — and the Bar — to get to know how to use it.”

I write about this in order to show how the common law was developed by great judges and Malaysia is a common law country. So that most of us will know how and why we have inherited a great deal from the English common law which is the cradle of it all. The common law is mostly the experience and the combined wisdom of great judges throughout history. It took the British judges 700 or so years to have their common law it is today. The US has a common law history of about 250 years. In Malaysia we have about 50 years since independence. Let us be humble and learn from the mistakes of others.

But for the moment it seems that our present crop of judges have stopped in their tracks as far as the development of the common law is concerned. Some of whom, especially those in the higher echelons, are sorely lacking in competency.

All that is needed now is for the judges to know how to use it

The Bar certainly knew how to use the new machinery to fight the abuse or misuse of power by the powers that be. But not so the judges of the Court of Appeal in Anwar Ibrahim v PP. But first, let me show you the relevant provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code that apply to this case. I start with section 418A(1) and (2), thus:

418A. (1) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 417 and subject to section 418B, the Public Prosecutor may in any particular case triable by a criminal court subordinate to the High Court issue a certificate specifying the High Court in which the proceedings are to be instituted or transferred and requiring that the accused person be caused to appear or be produced before such High Court.

(2) The power of the Public Prosecutor under subsection (1) shall be exercised by him personally.

This draconian piece of legislation gives the Public Prosecutor the power to transfer any criminal case triable by a subordinate court to a High Court of the Public Prosecutor’s choice. But who is the Public Prosecutor? For this we have to refer to section 376 of the Criminal Procedure Code. It reads:

376. (1) The Attorney-General shall be the Public Prosecutor and shall have the control and direction of all criminal proceedings under this Code.

(2) The Solicitor-General shall have all powers of a Deputy Public Prosecutor and shall act as Public Prosecutor in case of the absence or inability to act of the Attorney-General.

Subsection (2) allows the Solicitor-General to act as Public Prosecutor in case of the inability of the Attorney-General to act as such. This means that if the Attorney-General is disqualified to act on account of bias, as in this case, then in such a situation he is prevented from acting as the Public Prosecutor in a 418A application. In which case the Solicitor-General shall act as Public Prosecutor unless the Solicitor-General is himself tainted with bias — in this case for supporting the Attorney-General for what he had done that amounts to bias. But justice is still served as the defendant can still be tried before a subordinate criminal court. We are entitled to question the motive of the Attorney-General. Why should he, in the mantle of Public Prosecutor, be so insistent and selective in the choice of a court to hear the Anwar Ibrahim sodomy case? To everyone in this country the charge of sodomy against Anwar Ibrahim is no different from any sodomy charge against any other wrongdoer, unless, the Attorney-General as Public Prosecutor wants to have a particular High Court to hear the case against Anwar Ibrahim. But why so? What is so special about Anwar Ibrahim? Is he the Attorney-General’s or someone’s nemesis? Such an act creates an impression to the general public that the prosecution wants to ensure a conviction by choosing the correct court to hear the case. To all of us right-thinking Malaysians this is unfair and unjust treatment of anyone who is accused of a crime. If my reader has the patience to read this article to the end you will be shocked to learn of the real motive of the Attorney-General’s insistence on a High Court of his choice.

The judgment of the Court of Appeal in Anwar Ibrahim v PP

The judges of this Court of Appeal are Abdull Hamid Embong, Abu Samah Nordin and Jeffrey Tan Kok Wha JJCA. Remember their names for posterity so that the bad judges of this country will be etched indelibly in our memory. The judgment of the court was delivered by Hamid Embong JCA. It was a unanimous decision so that the travesty of justice caused by the decision implicates all of them. He said in his judgment which is in numbered paragraphs:

52. In signing this certificate, the PP cannot be said to be exercising a quasi-judicial function, but merely an administrative one, and one that only he can exercise. (see PP v Oh Keng Seng (1976) 2 MLJ)

53. In this case, we are of the considered opinion that the rule that a person under a suspicion of bias should not act as an adjudicator is not applicable to the act of the PP in signing this certificate. We would apply the exception that natural justice may be overridden by a statutory provision as enunciated in Franklin & Ors v Minister of Town and Country Planning (1948) AC 87, an exception which is applicable in both administrative and legislative processes.

54. We rule that, in this instance, despite the allegations of bias and conflict of interest against him, the PP being the specific and only officer authorised by law to sign the s. 418A certificate, may do so. His act cannot be impugned by reason of the imputed bias or conflict of interest. (see Mohd Zainal Abidin bin Abdul Mutalib v Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Minister of Home Affairs & Anor (1989) 3 MLJ 170).

Let me now expose the fallacy of the reasoning of the judgment of this Court of Appeal

In paragraph 52 (see above) the judge, Hamid Embong JCA, said that the Public Prosecutor was not exercising a quasi-judicial but an administrative function which only he as Public Prosecutor can exercise. This is not the law. The misuse of power may come from any quarter; it need not be from a person sitting in a judicial or quasi-judicial capacity. As Lord Denning has put it: “No one will suppose that the executive will never be guilty of the sins that are common to all of us. You may be sure that they will sometimes do things which they ought not to do: and will not do things that they ought to do. But if and when wrongs are thereby suffered by any of us, what is the remedy?” Nowadays there is always a remedy against the wrongdoings of public officials. The Attorney-General in this case is no more than a salaried civil servant — he is subject to the remedy against the wrongdoings of a public official. His employer is the Government of Malaysia and the CEO is the Prime Minister. On the other hand an English Attorney-General is a minister in his own right and an elected representative of the House of Commons.

In The Queen v Gaming Board for Great Britain, exparte Benaim and Khaida [1970] 2 QB 417, 430 Lord Denning MR said:

It is not possible to lay down rigid rules as to when the principles of natural justice are to apply: nor as to their scope and extent. Everything depends on the subject-matter: see what Tucker LJ said in Russell v Norfolk (Duke of) [1949] 1 All ER 109, 118 and Lord Upjohn in Durayappah v Fernando [1967] 2 AC 337, 349. At one time it was said that the principles only apply to judicial proceedings and not to administrative proceedings. That heresy was scotched in Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40, 77-79 per Lord Reid, 133 per Lord Hodson.

Ridge v Baldwin was a decision of the House of Lords. It was followed and applied by the Federal Court in Ketua Pengarah Kastam v Ho Kwan Seng [1977] 2 MLJ 152. This makes the common law decision of Ridge v Baldwin a part of the common law of this country.

So now we know it is utter rubbish to say that the principles of natural justice apply only to a judicial or quasi-judicial function. Ridge v Baldwin and Ketua Pengarah Kastam v Ho Kwan Seng have changed all that. And it is also rubbish to assume that only the Attorney-General can be the Public Prosecutor. See my explanation of section 376(1) and (2) of the Criminal Procedure Code which I have discussed earlier in this article.

Next is paragraph 53. In substance what this Court of Appeal is saying is that the Public Prosecutor is not an adjudicator so that the question of bias does not apply to him. As pointed out above that heresy has been scotched in the House of Lords’ decision of Ridge v Baldwin. He was merely doing his duty as Public Prosecutor, says the Court of Appeal, to put his signature which according to him is a mechanical act required of him by section 41 8A of the Criminal Procedure Code. But the question is, what if the Public Prosecutor acts in bad faith to transfer the case to the High Court of his choice? Surely, in such a situation the decision to transfer the case to a High Court of the Public Prosecutor’s choice cannot be allowed to stand on account of bias.

The Court of Appeal relied on Franklin & Ors v Minister of Town & Country Planning [1948] AC 87 where the headnote reads that the House of Lords has held that the Minister of Town and Country Planning has no judicial or quasi-judicial duty imposed on him, so that considerations of bias in the execution of such a duty are irrelevant, the sole question being whether or not he genuinely considered the report and the objections under the New Towns Act 1946. We know now that after Ridge v Baldwin in 1964, Franklin is no longer authority for any such proposition.

It is quite unbelievable that these judges of the Court of Appeal could ever dream of misleading the general public of this country by citing as authority a 1948 decision when they knew, as I am sure Haji Sulaiman or any competent counsel would have informed them, that Franklin is no longer good law. Not only that, Ridge v Baldwin in 1964 has been approved and applied by our Federal Court in Ketua Pengarah Kastam v Ho Kwan Seng, thus importing into the common law of Malaysia the English common law decision of Ridge v Baldwin.

Furthermore, they, the judges of this Court of Appeal, even try to mislead us by saying in paragraph 53: “We would apply the exception that natural justice may be overridden by a statutory provision as enunciated in Franklin & Ors v Minister of Town and Country Planning (1948) AC 87, an exception which is applicable in both administrative and legislative processes”. I have read through the judgment of Lord Thankerton, all 12 pages of it, many times over but I am unable to find the proposition of law that Hamid Embong JCA states in paragraph 53 of his “Outline of Reasons” was the ratio decidendi of Franklin. The Court of Appeal has put in words to the House of Lords’ decision in Franklin which were not found in the judgment of Lord Thankerton.

And now to paragraph 54. For the reasons given above, what the Court of Appeal says in paragraph 54 is not the law. Ridge v Baldwin in the House of Lords and our Federal Court in Ketua Pengarah Kastam v Ho Kwan Seng have scotched the heresy. If it can be shown that the Attorney-General had misused his power in the victimisation of Anwar Ibrahim that is enough to disqualify him from acting as the Public Prosecutor to sign the certificate under section 418A of the Criminal Procedure Code.

The most shocking condemnation of all

Finally, I will leave this to your own judgment. The following is taken from the judgment of Steve Shim, who was then the Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak in the case of Zainur bin Zakaria v Public Prosecutor [2001] 3 MLJ 604, 613-614:

To my absolute horror and disappointment Datuk Abdul Gani Patail used the meeting and the death sentence under s 57 of the ISA as a bargaining tool to gather evidence against Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim. He had with him the letter I had written to you and copied to him. He was waving the letter about and kept on saying, repeatedly, “I am not impressed” and suggesting that he would not be impressed with my plea to a charge under the Arms Act but instead he wanted more. This “more”, and it came across very loud and clear because Datuk Abdul Gani Patail laid it out in very clear and definite terms, was:

1. That Nallakaruppan was now facing the death sentence.

2. That there were other charges also under the ISA that he could prefer against Nallakaruppan but that if they (A-G’s chambers?) hanged him once under the present charge what need would there be to charge him for anything else.

3. That in exchange for a reduction of the present charge to one under the Arms Act, he wanted Nallakaruppan to cooperate with them and to give information against Anwar Ibrahim, specifically on matters concerning several married women. Datuk Abdul Gani kept changing the number of women and finally settled on five, three married and two unmarried.

4. That he would expect Nallakaruppan to testify against Anwar in respect of these women.

I was shocked that Datuk Abdul Gani even had the gall to make such a suggestion to me. He obviously does not know me. I do not approve of such extraction of evidence against ANYONE, not even or should I say least of all, a beggar picked up off the streets. A man’s life, or for the matter, even his freedom, is not a tool for prosecution agencies to use as a bargaining chip. No jurisprudential system will condone such an act. It is blackmail and extortion of the highest culpability and my greatest disappointment is that a once independent agency that I worked with some 25 years ago and of which I have such satisfying memories has descended to such levels in the creation and collection of evidence. To use the death threat as a means to the extortion of evidence that is otherwise not there (why else make such a demand?) is unforgivable and surely must in itself be a crime, leave alone a sin, of the greatest magnitude. Whether his means justify, the end that he seeks are matters that Datuk Abdul Gani will have to wrestle with within his own conscience.

You can read the rest of it from the law reports. I cannot stomach this anymore. Possibly you can approach a website to show the entire judgment of Shim CJ on their portal with the permission of MLJ or any other law report.

All I can say is that, if Gani Patail is a member of an Inns of Court he would be disbarred as a barrister.

I am sickened by the perversity of the office of the Public Prosecutor.

N.H. Chan

1 comment:

Blame it on Mahatir.

Had he never been born we would not descend to such a plight.

Do we still have any moral left?

Post a Comment